Tuesday 18 November at the School of Slavonic and Eastern European Studies at University College London saw the event the Balkans, its Diasporas, and the Stories of Material Culture being held, hosted by an amazing panel of presenters.

Curator and Founder of the Balkanism project, Arbër Qerka-Gashi, gave a wonderful account of the significance of material culture for Balkan communities within British diasporas, that also applies to all other diasporas. “Objects and material culture play a vital role in shaping cultural identities. From everyday items used in cooking or photo albums depicting the history of a family, to more sacred cultural and religious artifacts used in important rites, these objects carry powerful narratives, stories, and personal experiences. They embody the ways in which we come to know, express, and experience our own cultural identities.” Arbër started by giving the Susan Sontag quote “To collect photographs is to collect the world” and explaining the significance photos have with memory and identity. The picture of his parents in 1987 Kosovo as a young couple displayed an undeniably Yugoslav aesthetic, looking much like most other young people from Slovenia to Macedonia and everything in between. Arbër also showed the “jelek”, a vest worn by women throughout the Balkans, that his mother wore when she was married. Jeleks like that can be seen for sale in boutiques in market places particularly in Muslim-populated areas of the Balkans, such as those in the Ottoman-era grand bazaars in Prishtina, Novi Pazar and Skopje, though the one that Arbër’s mother had was a unique quality to it.

Mirela Xhaferraj, who also was my Albanian language teacher, presented a very intriguing item – a bread stamp. Mirela, who comes from the Orthodox Christian Greek minority in southern Albania around Sarandë, explained how the bread stamp she has came from her great-grandmother and had been handed down through the generations. Bread stamps like these are used on special loaves made for Orthodox Christian celebrations such as Easter and the major saint days. There were two aspects, however, that made this bread stamp quite extraordinary. One was the patterns that appeared on it, where there was no discernible order nor was there clear markings showing “IC XC NI KA”, Greek for “Jesus Christ conquers”, that typically appear on such bread stamps in the Balkans. The other aspect was that it has actually survived! As a kitchen implement, it dates well before the time when in 1967 during the throes of its own Maoist Cultural Revolution, Enver Hoxha, supreme leader of then strictly Stalinist Albania, declared the country to be the world’s first fully atheist state. Everyone was supposed to give up their household religious items, whether it be religious books, icons, pictures, etc. and have them destroyed. Until religious practice was again permitted in the final stages of Albanian communism in 1989, possession of any religious item in Albania was a serious crime, so Mirela’s family having held on to this bread stamp was a feat of bravery. Mirela later recounted that as a child during that time, she once was walking with her grandmother past the ruins of what was their village’s Orthodox Christian church. In a stealthy move, Mirela saw that her grandmother did something she had never seen before – her grandmother crossed herself, as is the custom for believers of the Orthodox Christian faith whenever they pass a church. Mirela noted that such a move and in front of a child, i.e. someone who could have innocently revealed to someone else what had happened and unwittingly caused her grandmother to be in a lot of trouble with the authorities, was a firm display of trust. Mirela said that was the first time she had been witness to a visual sign of another way of thinking; one that was not sanctioned by the Party. Quite an astounding story!

Ramona Gonczol, the Associate Professor in Romanian language studies at SSEES, introduced us to the white ceramic pottery using the unique white clay of the region from where her grandmother lived in Romania close to the Hungarian border. And Macedonian and Slovenian teacher, and my sister from different parents, the vivacious Ana Ilievska-Završnik, brought in a broom (metla) and a long rolling pin (sukalo) used primary for making kori i.e. the thin filo pastry used to make Macedonian (and Balkan) pies and pastries such as burek and baklava. However, these kitchen utensils have other powers in that they are also, dare I say, torture tools not only to mould dough but also behaviour. With a prior warning of impending domestic violence, Ana showed the significance of these kitchen items with the Macedonian and wider Slavic legend of Baba Roga/Yaga, as well as how there are Macedonian stories for children where beating the living daylights out of those supposed worst of all evils – lazy wives and disobedient children – is perfectly just. By the way, I found out that Ana lived next door to Macedonia’s comedic-actor power couple, Gjorgji Kolozov and Shenka Kolozova. Here they star in the 1990 TV Skopje production of Macedonian Folk Tales – the Lazy Wife and the Broom.

What made this sell-out event even more special was that it was completely interactive; we all could be participants during the show-and-tell segment. Whoever was willing could present their own personal objects and explain to the audience how this item represents their identity, culture and/or experiences.

Guess who was first to volunteer to show their item – yes, yours truly.

OK, so I cheated and brought two polarly opposite items, to show how the extreme coexisted, and also snuck in a third.

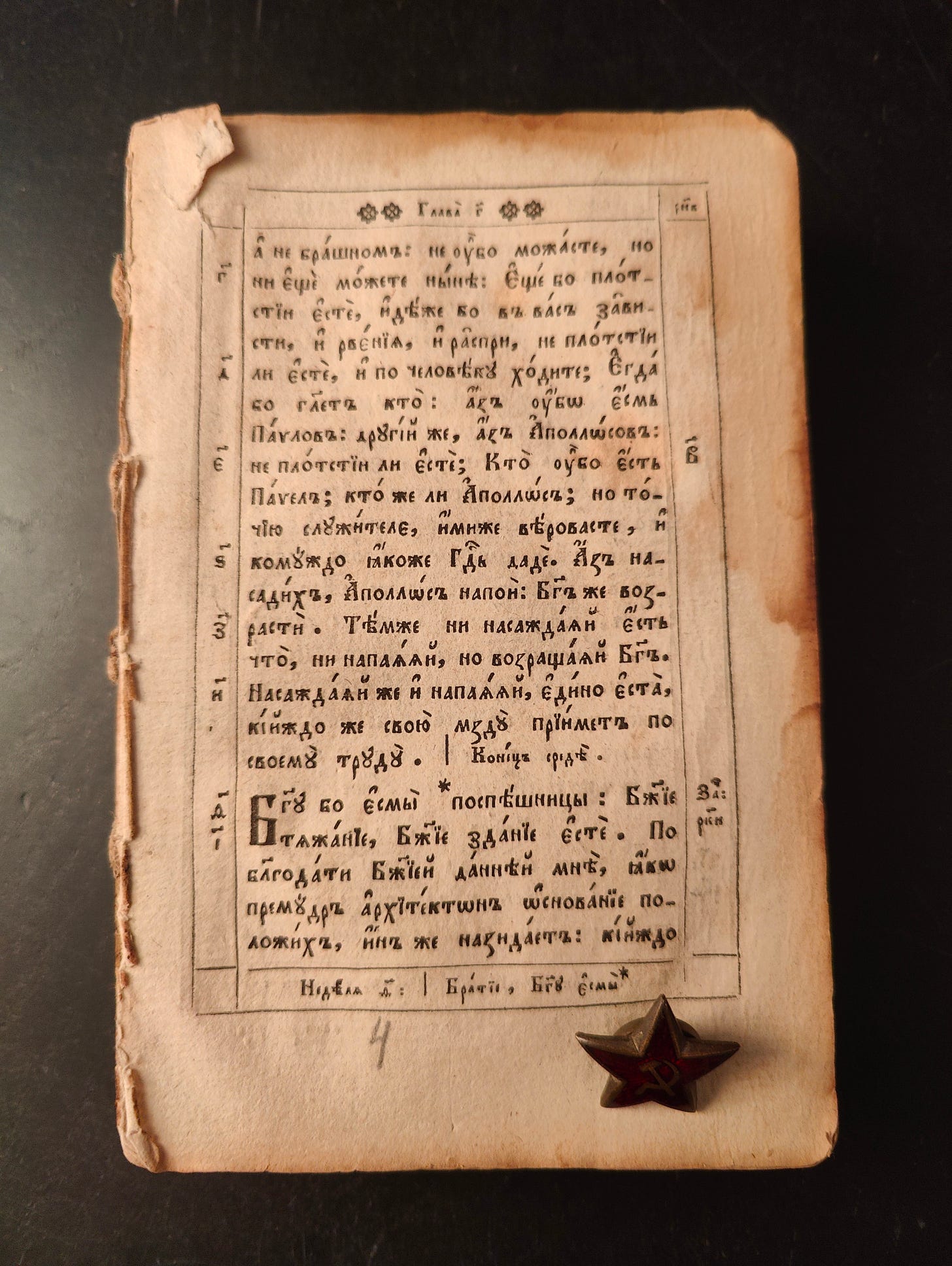

One of the items I brought was something that had been presented to me only last year – a tattered old book missing its cover, so it was hard to properly ascertain what this book actually is, but one thing that is for certain is that it is written in Old Church Slavonic.

Old Church Slavonic was the first written Slavic language attested in literary sources, and for over a millennium has been the main liturgical language of Orthodox Christian churches throughout the Slavic world, though its use has progressively waned in favour of the modern, standardised languages represented by that titular church (e.g. Serbian for the Serbian Orthodox Church, Bulgarian for the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, etc.). The language is believed to be based on the Slavic dialect as spoken in the area around Salonica, Macedonia, now in northern Greece, in the 9th Century CE. So in other words, it can be described as medieval or old Macedonian. The “Salonika brothers” Saints Cyril and Methodius propagated the language as the main weapon in the conversion of Slavic-speaking peoples to Christianity. While for centuries it was the common literary language for all Slavic-speaking peoples, it’s best considered as the Slavic Latin; whereas spoken Slavic languages continued to develop and, in the process, diverging immensely, Old Church Slavonic remained frozen like a time fossil. Its use, as the name prompts, is almost exclusively religious, and so that indicated that this book was solely theological-related.

Now I thought that I had a good idea of all the books we had in our family. As a voracious reader as child, I had pretty much read all the books we had at least twice, and the number of books we had from the Balkans, whether they be in Macedonian, Bulgarian or Serbo-Croatian, was relatively limited. That made being presented with this book a bit of a surprise. I asked my father where did this book come from and he told me that a great uncle of his had this bestowed to him in the 1930s when he was in a seminary in Macedonia in then Royalist Yugoslavia, however he wasn’t truly sure of that. What was for certain is that my father was so taken by this book when he was young that it was part of his few belongings that he brought with him to Australia when he left Yugoslavia in the early 1970s. By the way, the brown suitcase, just the one and, as was the case at the time, with no wheels, that he had with him when he migrated to Australia remains on display in the lounge room of my parents’ place – a constant reminder of what little my father started off with when he started his new life on the other side of the world, juxtaposed within the context of what he has now.

I accepted this book primarily because I know of an academic who is currently researching about the role of the Orthodox Church in Yugoslav Macedonia between the world wars, so here was a copy of an actual book used from that very time period. I thought he would love to have a hold of this book.

This academic told me that he would make further investigations about the history of the book and consulted an expert in Balkan religious books. The findings were that this book dated much earlier than the 1930s! Based on the binding technique used and the quality of the paper, it’s more than likely that this book dates from the 1880s and was printed and bound in Ottoman Constantinople, which at the time was also the seat of the relatively new Exarchate Orthodox Church in the Ottoman Empire, the liturgical language of which was Old Church Slavonic. So I have a 140-year-old book in my hands - a rare find considering the dearth of books at the time in Macedonia given the then shockingly low literacy rate in the Ottoman Empire.

But why keep this book secret then?

My father is not one these days to willingly answer probing questions when interrogated. Instead, he’ll deliberately do the Balkan inat thing and deflecting any query, making investigation into simple matters a mission impossible. Instead, he’ll decide on his own time and accord when he’ll offer that information, making him the complete gatekeeper of a treasure chest of history.

However, I do speculate that this behaviour of secrecy regarding religious texts comes from the environment in which my father grew up in – 1950s Yugoslavia, when the Communist Party was finally making inroads and stamping its rule on the provincial areas. This meant anything to do with religion was discouraged and doing otherwise could be grounds for denying career progress down the track, especially when membership in the atheist Communist Party was a necessity if wanting to get to the top of any field. Granted, the situation in Yugoslavia was nowhere near as extreme as in Albania at the time, but it was quite clear to the Yugoslav masses that if you want to be religious, it was best to make it a private matter only.

This book then represents for me a lost past; a testament of the culture of silence that is a common feature with family histories in the Balkans. Quite often people in the Balkans are unwilling to talk about the past, and there isn’t anywhere the near same interest in family history and ancestry like there is in western countries. This prevailing attitude counteracts the otherwise intense interest and knowledge in the region for state-sanctioned, cherry-picked and highly glorified national histories, where the only negative aspects that get emphasised are ones that perpetuate a national sense of victimhood and injustice, one that can then justify acting in vengeance or, as we have seen time and again and in recent times, provide poorly grounded excuses to commit crimes such as genocide. Not that this is uniquely Balkan – it happens worldwide and is unfortunately an indelible part of the human experience.

The other item I did bring was the red star with hammer-and-sickle symbol from my father’s “Titovka” hat worn as part of his uniform when he served in the Yugoslav People’s Army in the late 1960s. I’ll go into details about the significance of this another time very soon.

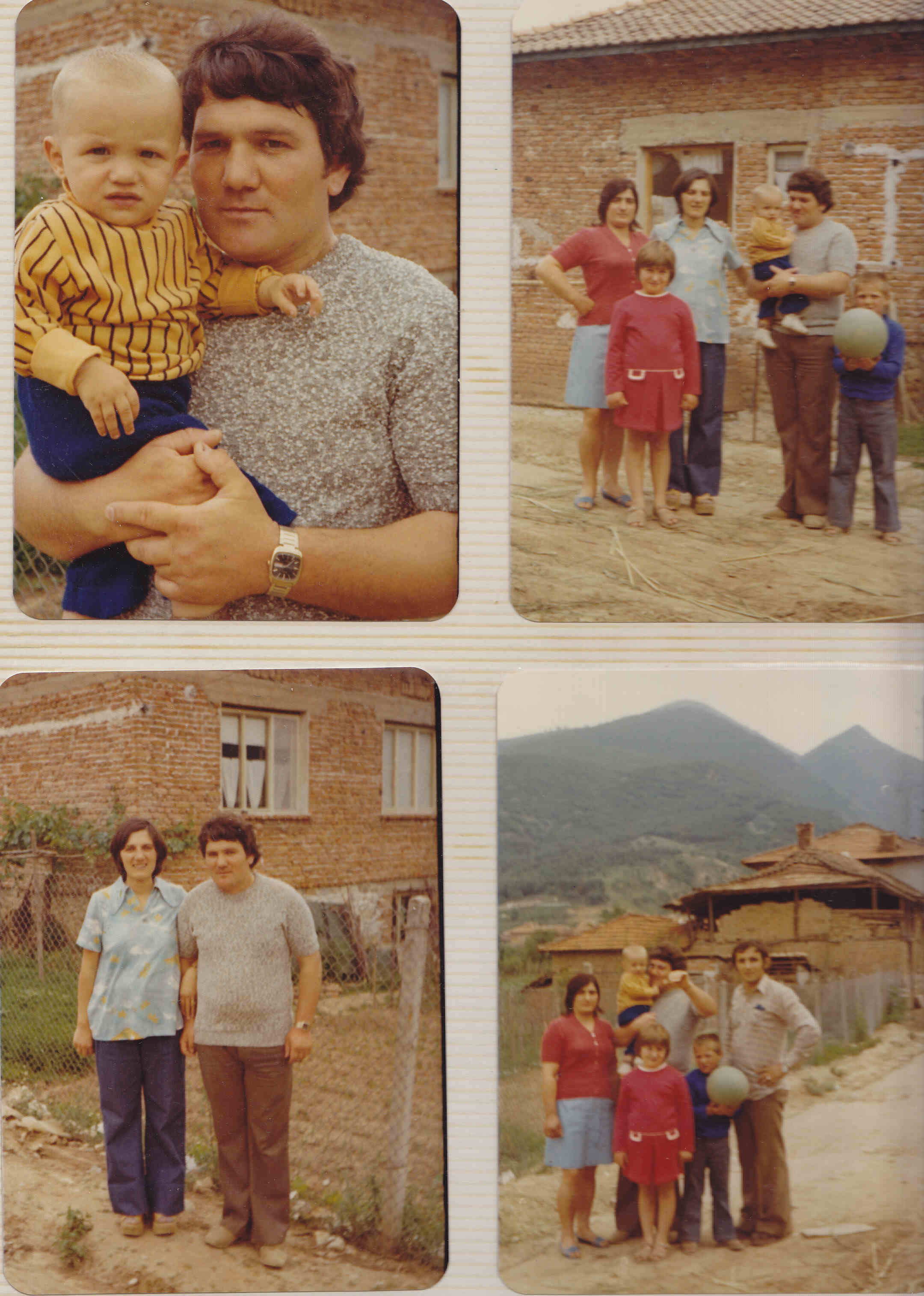

The third item was not something I had planned nor did I have it with me but was prompted when Arbër talked earlier of the significance of photos and memory. The week before, I had spent a few days reconnecting with Vasil, a long-lost second cousin of mine in Bulgaria. Our common link is that we have the same great-grandparents – his grandfather and my grandfather were brothers, however in 1947, after my grandfather had been arrested for aiding what was described as a separatist movement… and then making a daring yet successful daytime escape from a Bulgarian gulag camp over the border into Greece and later making his way to Australia, the brothers were never to see each other again.

In 1976, my grandfather’s daughter aka my mother went to visit Bulgaria for the first time in her life and was able to see all the relatives from her father’s side of the family that she had hardly heard about. Along with her went my father and a little baby – me.

At the time in tightly controlled, communist Bulgaria, citizens hosting relatives especially from evil capitalist countries such as Australia, and more so those who were deemed part of what the Bulgarian communist authorities then labelled as “the hostile emigration”, was fraught with danger as the repercussions for Bulgarians in such close contact with foreigners could be severe, notwithstanding raise the suspicions of local security forces. For that reason, most of our relatives reluctantly could not have us stay at their places, causing great dishonour and embarrassment to them as this violated the traditional norms for hospitality. However, one family did bite the bullet (pardon the pun) and have us over; it was that of Ivan, the youngest son of my grandfather’s older brother. Ivan and his wife Milka had two sons – Lazar, named after his grandfather, and Vasil, who like me was also a little baby at the time.

Naturally, we recorded our time with our relatives with photos, though with my father being absent from all of the pictures we took, it would suggest he was designated the photographer. I have no recollection of that time (unlike when we were in Bulgaria again in 1980 – I have very vivid memories of then), but the photos remain and, luckily, so too the info that my mother provided me years ago when the whole experience was still clear in her mind.

Fast-forward almost 50 years from that meeting, and my mother received a Facebook friend request from a young woman named the same as her maiden name. My mother at first thought it was some internet bot that had stolen her personal details, but a quick investigation found that this woman was legitimate – it was the daughter of once little baby Vasil. My immediately family immediately connected with them, but as I’m the only one who can write in Bulgarian and these long-lost relatives are not that confident with English, I was assigned the role of official family spokesperson and conduit, something that I’ve been doing now for decades, facilitating communication between family in the Balkans and Australia.

It turned out that Vasil, who’s the same age as me, bucks the trend with most of the rest of our rather quiet and shy relatives in Bulgaria in being quite the talker. He’s also an avid genealogist, so he had information about the family I had not heard of before.

So when the opportunity came to go back to Bulgaria for a visit, Vasil insisted at the point of kidnapping me that I stay at his family’s place in the town of Elin Pelin, just to the east of the Bulgarian capital, Sofia. I ended up spending 5 days witnessing how he and his family live, and we had plenty of time to swap stories and family trees.

Here’s what I found out:

- Our grandfathers had an older brother, Stoyan. I had no idea of this brother, but that then makes sense as to why my grandfather named his only son with that name. In 1924, Stoyan was shot along with 16 others in a massacre known as the Tarlis Incident. The resulting international outcry from this massacre even prompted the League of Nations into action.

- Vasil had no idea that our grandfathers had a sister called Anastasia (i.e. Asya). What had happened to her is that she married a man who had also been involved with the same movement as my grandfather and, likewise, was arrested and sentenced. As punishment, his wife and, after being released from the Bulgarian gulag, he were sent away to internal exile to a remote village on the other side of Bulgaria, but they later moved to the northern Bulgarian industrial city of Pleven. In 1976, she and her son, daughter-in-law and two children drove down from Pleven to Gotse Delchev to see us, but because of the negative fallout from Asya’s husband’s being a former political prisoner, the rest of the family cut all contact with Baba Asya and her family after that.

- Apparently, my grandfather’s first wife had also been threatened with internal exile after my grandfather had been arrested. She instead opted to be banished to a neighbouring village (she had been living in a nicely appointed flat in the regional city’s former Jewish quarter), which the Bulgarian communist authorities treated essentially a dumping ground for people deemed “politically unreliable” and ended up marrying the village drunk. She didn’t have a pleasant life.

- I found out more details about my grandfather going AWOL from the Nazi-allied Bulgarian Army during WWII. Apparently Bulgarian military police arrested him because he stole a bag of rice to give to a starving Jewish family in Niš, Serbia, which was under Bulgarian Army control at the time. However, in a move that he was to repeat a few years later, my grandfather escaped from prison and made his way back to his hometown to marry his sweetheart before being caught again.

- Our relatives did not get off scot-free after our visit in 1976. For years, Vasil’s father Ivan had to report to the local police station on a monthly basis, where he’d be interrogated about his connections and any correspondence with us in Australia. The local security forces made it clear to Ivan that the contents of all letters being sent from Australia to him are being intercepted and inspected, and that he’s not receiving most of them. Vasil recalled as a child that one time one letter from us in Australia did arrive at their house… but it was clearly open. This served as a reminder to Ivan of who had the upper hand.

- As westerners from the decadent west, our arrival in 1976 in the provincial town of Gotse Delchev, where most people had never seen a foreigner in their lives, was quite an “event”. Word had it with Vasil’s neighbours that my mother arrived wearing “a big hat”, which is a bit strange as my mother has never been the hat-wearing type. People apparently admired the high quality of our clothes.

What brought much cheer for Vasil was when I presented him with some photos from the time we met as babies in 1976. I actually couldn’t identify most of the people in the photos, so I just scanned those that I knew were from that time. Many of the photos turned out to feature his late parents Ivan and Milka (both died in their late 60s due to cancer), his older brother Lazar (who now has severe schizophrenia and is housed in a mental health institution) and Vasil himself. I showed him the photo of him in his father’s lap while in our presence… and Vasil started to cry. Actually, he couldn’t stop staring at that photo, despite the tears in his eyes. He later told me that he has just one photo of himself left from when he was a baby and that, like all photos at the time in Bulgaria, is in black-and-white. This photo though was special; it’s in colour, and was taken at a time when colour photography in Bulgaria was technology only available for high professionals. Vasil has been telling me he’s been spending hours staring at that photo. He’s mesmerised! He now sees his young innocent self in colour.

But this had me wondering… surely we had sent copies of these photos to them? Our other relatives in Bulgaria had copies of the colour photos we took when we went in 1976 and 1980. So why didn’t they? And then I remembered what Vasil told me about the interrogations his father underwent and how he was told that they weren’t getting all the letters. The Bulgarian authorities must have seized and confiscated those letters with our colour photos.

Vasil didn’t get to have that colour photo of himself then…

But he has it now!

If you’re interested in all things Balkan and you haven’t signed up yet, then do yourself a favour and follow Balkanism on social media. Also, if you’re interested like I am in the languages and cultures of Central, Eastern and South-eastern Europe and Russia, then keeping a pace with what’s happening with PROLang is highly recommended. And if you’re in and around London, then do come to the regular seminars held at UCL SSEES. I’m a regular, so come and say zdravo!

.%20A%20day%20of%20campaigning%20%E2%99%80%20%E2%80%A6%20or%20a%20day%20to%20buy%20flowers%20%F0%9F%92%90.jpg)