Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, Montenegrin... they're all the same, right?

Whenever I reel off my list of working languages, I won't lie, it sounds impressive, but I have the bloody breakup of Yugoslavia to thank for making that list longer than what it was.

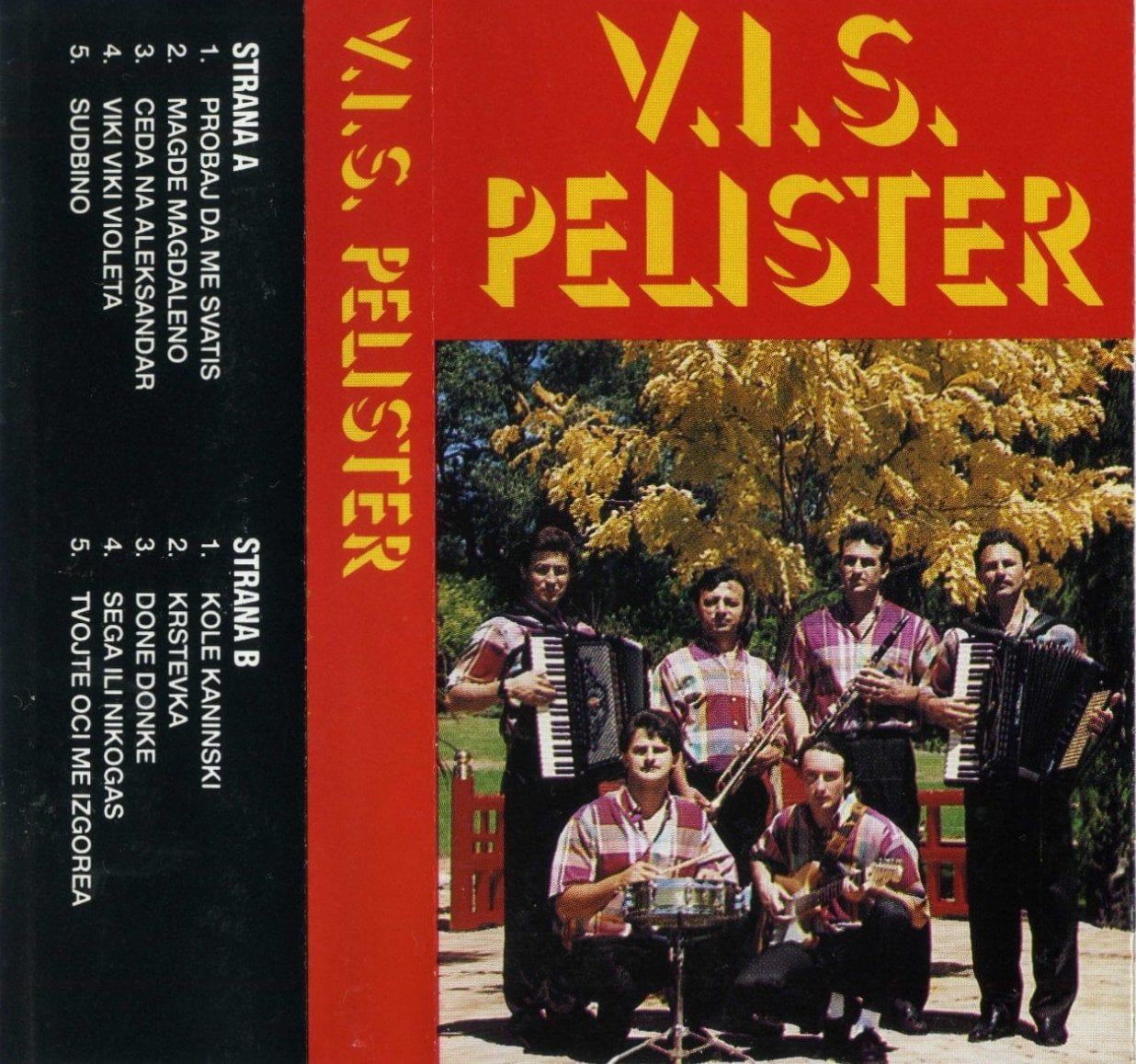

Until 1990, there was the one (official) language: Serbo-Croatian. After that we had two: Serbian and Croatian, then there was Bosnian, and in 2006, after Montenegro became an independent country, Montenegrin. I joke that my list could grow longer if any more countries break away.

So is there much difference between them?

In conversation, hardly any. People who speak any of those four languages can easily understand each other as if they're still speaking the one language. Sure, there might be a word or two that might confuse others (particularly in Croatian) but nothing too major. Think of it in the same way that there are differences in vocabulary, meaning, accent, references, humour, tone, etc. between the many spoken variants of supranational languages (English, French, Spanish, Portuguese…) but general chit-chat poses very little barrier.

The differences become more apparent when in writing, especially when using the official standard versions of these languages in more technical and especially administration-related texts. It’s here where the changes are growing.

Whether they should be described as dialects or variants rather than separate languages has been debated for decades, even before they broke ranks in 1990. For even during the days of Yugoslavia, each of the republics where Serbo-Croatian was official had their own standard variant, the forbearers of the separate languages of today. But if there has ever been a greater case proving Yiddish scholar Max Weinrich’s blunt quip that “a language is a dialect with an army and navy”, then look no further than Serbo-Croatian and its successors.

Unfortunate to say but the Yugoslavs were warned!

Legendary 1980s Sarajevo comedy skit show Top Lista Nadrealista lampooned at the time what seemed the ridiculous concept that Serbo-Croatian could splinter into numerous languages. What at first seemed a joke ended up being an unfortunate case of life imitating art.

It was a major shock when they did officially become “separate” languages… and more so when some of the zealot supporters of this move behaved as if they were so.

This was my first case…

As Yugoslavia was descending into breakdown in 1991, I was at high school in Australia, where we had our own group of Yugoslavs. At the time, we had no idea who among us was Serb, Croat, Bosniak, etc. as it simply was not important up to then. They knew I was Macedonian though as my Serbo-Croatian then was nowhere near as good as the rest of them. But we knew things were seriously going bad in Yugoslavia, and that we weren’t immune to it tens of thousands of kilometres away, when one guy in our group told us about what had happened to his father, a Serbo-Croatian interpreter, the day before. He had been on a job and his client was a woman originally from Croatia. As is practice with interpreters to familiarise themselves with the speaking style of their clients, my friend’s father started a simple introductory conversation with the woman he was to interpret for. Soon enough, the question of “where are you from in Yugoslavia” came up. His father said he was Vojvodina, to which the Croat woman unhesitantly replied, and in all seriousness:

“Ah, so that’s why I couldn’t understand you”.

We were horrified at this! This response was obviously politically motivated as it was impossible for her not to have understood my friend’s father. I mean, she had no problems talking to him up to then. Little did we know at the time that such sentiments shared by this lady was only the tip of the iceberg. We truly had no idea what awaited Yugoslavia, but we could see that madness was going to play a huge role.

When people would say “But these languages are all the same, right?”, my response for many, many years was:

“Yes… but use the wrong word with the wrong person and they might kill you.”

A bit too much?

Well...

“Coffee” is one of only a handful of words different (albeit slightly) in Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian. Linguists Marko Dragojević and colleagues recount the story of a cafe in an area of Bosnia and Herzegovina controlled by Croats during the 1992-95 war. On its menu, the cafe offered its customers coffee at three different prices, depending on which word customers used to order the item:

- Kava, indexing a Croatian, and by extension, Catholic identity, was sold for the modest price of 1 Deutsche Mark.

- Kafa, indexing a Serbian and Orthodox Christian identity, was not available for sale.

- Kahva, indexing a Bosniak and Muslim identity, cost the customer a “bullet in the forehead”

OK, that’s extreme, but it’s the most blunt display of how sensitive language being a marker of national identity can be not just in the Balkans but all throughout the world (Québec anyone).

To avoid having a virtual bullet to your forehead, if you do need something written into any of the successor languages to Serbo-Croatian, a person who truly translates into only one out of the four must be employed, i.e. a Croatian translator for Croatian, a Montenegrin for Montenegrin. Anyone claiming they can translate into all four languages is a con as it’s impossible to know of all the latest nuances between the languages. And trust me, there are keyboard warriors to government officials out there ready to spot an offending word (even if they do understand what it means regardless) and defend the national interest to the bitter end. I’ve seen government officials in the region reject giant projects and investments worth millions all because of a “wrong” word appeared in official documentation and submitted applications.

Bullets notwithstanding, with oral communication between the different languages being relative seamless most of the time, how then to call this joint oral language? Calling it “Serbo-Croatian” won’t win you many friends, particularly as it officially no longer exists. For some, the term is so associated with (socialist) Yugoslav times that it can be quite offensive. After all, the question whether Serbo-Croatian is even a language was one of the core issues of the Croatian Spring of 1967-71, Yugoslavia’s most significant post-WWII political crisis that threatened the very fabric of the federation.

People from ex-Yugoslavia in diaspora communities, especially in western Europe, have found a convenient work-around to describe their joint spoken (not written) language – “naš jezik”, literally “our language”, because… it is. It’s definitely easier to say than listing all four languages, which frankly is a complete word salad!

Montenegrins and (to a lesser extent) Bosnians also use this euphemism as a safe way to negotiate the delicate issue of how respondents recognise the language they speak, especially as there are often no apparent clues to denote the ethnicity of the speaker, and it can take some time until a distinguishing word comes in conversation. In Montenegro’s case, to reflect the competing patchwork of ethnic identities in the small mountainous country, the constitution enshrines Crnogorski (Montenegrin) as the “official language” and (along with Albanian) designates Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian as “languages in official use”. However, these three languages when spoken in their Montenegrin variants are identical to Montenegrin, so “naš jezik” works best here to describe what they’re all speaking. Though interestingly, when using ATMs in Montenegro, the language options usually state ‘Montenegrin’ in Latin script and ‘Serbian’ in Cyrillic script.

The problem with the term “naš jezik” is that you have to be “naš” i.e. “one of us” to use it. It’s perfectly fine for people who grew up in a “Yugoslav” environment, e.g. in pre-1990 Yugoslavia or in some (definitely not all) of the “Yugoslav” environments in the diaspora, where Serbs, Croats, Bosniaks, Montenegrins and everyone in between intermingles as they find they have more in common with each other than with the majorities of their countries of residence.

But talking about “naš jezik” with a close translator colleague of mine, a Croat born after the fall of Yugoslavia and raised with a strong Croatian identity (as was the case in the 1990s and 2000s Croatia), he doesn’t feel that he has that level of commonality with Serbs, Bosniaks or Montenegrins to consider them as fellow speakers of his native Croatian to warrant the use of “naš jezik” with them. He admits, of course, that he understands Serbian, Bosnian and Montenegrin perfectly… but that’s as far as it goes. He’s hardly unique in this; actually, for the generations born and raised in the past 35 years since Yugoslavia’s unravelment, this is the attitude that prevails. Separate countries with separate paths of progress does this.

While much is ridiculed of the changes to these languages that have occurred these past three decades, which especially in the case of Croatian has often been top-down and politically motivated, many in ex-Yugoslavia are truly unaware of to what extent “their language” has changed in the other republics.

Take for instance something as simple as “zdravo”, the former pan-Yugoslav word for “hello”, which could be used from Triglav in northern Slovenia right through to Gevgelija in Macedonia on the border with Greece. The word still means as it was in Serbian, Bosnian, Montenegrin, Macedonian and (depending on dialect) Slovenian, particular since 1991 Croats have adopted the use of the formerly Zagreb-specific greeting “bok” as a replacement. Many Croats now consider “zdravo” either to be too “communist” (the word essentially means “healthy”, so how that equates to communism, I don’t know) or too “Serbian”. And yet, still to this day when other ex-Yugos visit Croatia, you’ll hear them say “zdravo” only for Croats to cringe. Best tip: stick to the more formal “dobar dan” – at least that hasn't changed and applies for all four languages.

- No, we speak Croatian and they speak Serbian.

But you understand each other?

- Yes, well, it’s the same language.

One question I'm often asked, particularly from people in ex-Yugoslavia, is if it no longer exists, then why do I still list Serbo-Croatian as a language I translate from?

The main reason is because I still receive many requests for translation from “Serbo-Croatian”.

When it involves historical texts or documents that pre-date the 1990s, they are absolutely justified to state as such. But many of these requests come from people who are not from the region and are simply unaware that the term “Serbo-Croatian” is obsolete, anachronistic or, as we’ve seen, offensive. Hey, I've even received requests to translate from “Yugoslavian”! I can assure you that there's never been a language with that name.

So apart from “naš jezik”, which we’ve seen is restricted to use by native speakers, is there really an alternative term that can be used when you know the text comes from ex-Yugoslavia but don't know exactly in which out of the four successor languages?

You can do what some international organisations do and use initialisms. I like using “BCSM” (yes, for the lolz) and the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia used “BCS”. The plus is that saves from writing out the names of all four languages, but the minus is that hardly anyone except professionals working in these languages will understand what you mean.

In the end, there’s no easy fix except to ask the person what language it is.

Serbo-Croatian was devised in the 19th century as a way to unify people, and over two-hundred years later it still does… just. It’s such a shame that this unifier has split to represent that other aspect of 19th century politics, the nation-state. Language play a central role in the forming of a national identity and people can be very defensive about this. Meanwhile, I’m somewhat ambivalent to it all. I appreciate how fortunate I was to have grown up at a time when the peoples of Yugoslavia were theoretically at one and had their joint language to have them be able to express their thoughts on the same footing, and yet I’m sad that’s almost all gone now, especially considering the horrible circumstances that have led us to this state. But on the other hand, I know that nothing stands still, and that includes language. It is what it is, and as many the region have said many a time, had we been better people, perhaps all of this wouldn’t have happened. Still, I hope that this “jezik” remains “naš” for as long as possible, for everyone’s sake for we know how tortured it can be when we don’t have our safe word.

.%20A%20day%20of%20campaigning%20%E2%99%80%20%E2%80%A6%20or%20a%20day%20to%20buy%20flowers%20%F0%9F%92%90.jpg)