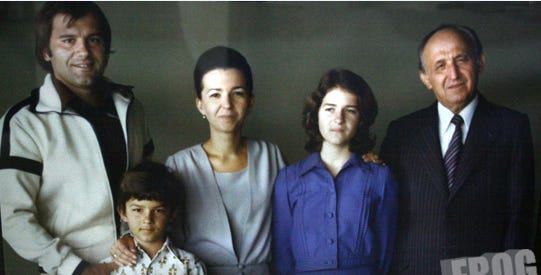

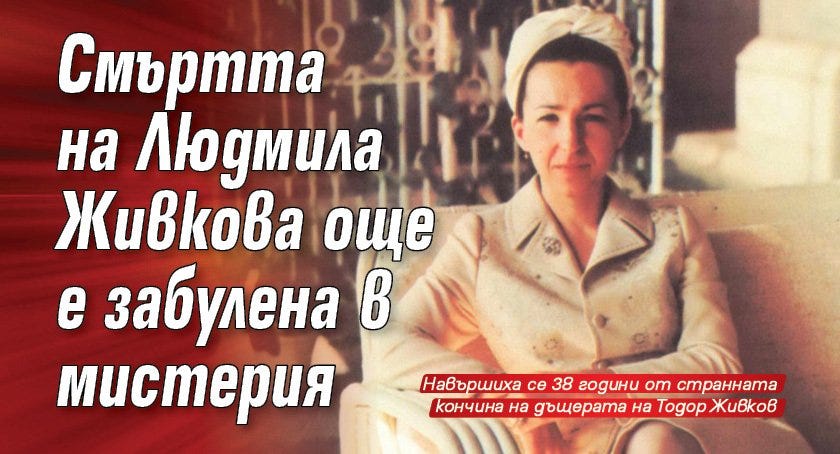

At noon on 21 July 1981, Bulgarian national radio interrupted its broadcast to announce that Lyudmila Zhivkova, the country’s de facto culture minister, daughter of Bulgaria’s then-paramount communist leader Todor Zhivkov, had died suddenly. Another five days and she would’ve turned 39. Bulgaria’s populace couldn’t believe what it had heard, though rumors had already been circulating that she had passed away. This was big news as not only was she the paramount leader’s daughter, she was high-profile. The young Zhivkova was then one of only two women in the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party. Most of all, the young and highly ambitious Zhivkova was generally believed to be first-in-line to take over the reins from her father in a communist dynasty. La infanta, have you be. Zhivkov Senior at the time was 70 years old, which might not see that old these days, but when you look at allied USSR in the 3 years following Zhivkova’s death, Brezhnev died at age 75, Andropov at 69 and Chernenko at 73, the writing was on the wall for Bulgaria’s “Tato” (“Daddy”—one of Zhivkov’s many nicknames). This is why Zhivkova’s untimely death, like that of any anointed successor cut in their prime, was such a shock in Bulgaria.

Over 100,000 people turned out for Zhivkova’s state funeral, which one one member of the Zhivkov clan fancifully described as the “burial of hopes”. Not since the funerals of the country’s King Boris I in 1943 during WWII or of the country’s first communist leader Georgi Dimitrov six years later in 1949 had Bulgaria seen such a turnout.

Neither is it coincidental that King Boris, Dimitrov and Zhivkova all died suddenly under mysterious circumstances. Speculation started to fuel immediately with Zhivkova’s death as few believed the official version of a sudden death after “a short illness”. Bulgarians at the time only had access to either the official censored media or illicitly by hearing foreign shortwave radio, so rumours and hearsay filled the information vacuum, and in turn giving more weight to the often otherwise flimsy veracity of their content. Talk of Zhivkova’s death goes immediately into claims of suicide or murder, and there are worthy grounds in either case. So much that many Bulgarians question the official line that many even doubt the official time and date of her death. An autopsy was performed, the results of which have remained a state secret ever since, and the doctors who performed it were later silenced—circumstances that just give greater credence to the conspiracists.

Prior to her death, Zhivkova herself had repeatedly told those close to her that she was being watched and that her end was near. There’s nothing particularly surprising that she was being watched though—leadership circles are often full of power struggles and paranoia, so spying on the immediate competition is practically a given. But who would dare want to threaten the second most powerful person in the country, let alone most powerful person’s daughter? In the 25 years to date of being in the top job, Todor Zhivkov had consolidated almost all power in his hands, and with the rapid rise of his daughter, he laid the foundations for a communist dynasty and the (positive) posthumous continuation of his legacy. But even dictators don’t believe they are all-powerful. In Zhivkov’s case, he had many other factors to account for – not just Bulgarian public opinion (yes, even in dictatorships this still mattered as the stakes were all or nothing) but also keeping the Kremlin happy, the ultimate political, economic and, most of all, military lifeline for the ‘brotherly’ Eastern bloc countries. And at that time, the Soviet leadership under an ailing Brezhnev, along with the Eastern bloc allies, were not particularly happy with Bulgaria’s internal politics. But it wasn’t Zhivkov’s perceived plans for dynastic succession that was problem but with his daughter’s highly unorthodox policies and ambitions.

Who was Lyudmila Zhivkova and how did she rise to become Bulgaria’s Number 2?

Zhivkova was born in the village of Govedartsi, south of the capital Sofia, to communist guerilla parents during WWII in fascist Bulgaria. The Soviet Red Army’s entry into Bulgaria in 1944 saw the Bulgarian communists placed into power, and her highly decorated parents were immediately propelled into Bulgaria’s new political and social elite. With access to the best education on offer in Bulgaria, Zhivkova later studied history at Sofia University and art history at the very prestigious Moscow State University. The pinnacle of her academic endeavours was in 1970, when at the age of 18 she researched for a book on British-Turkish relations at Oxford University in the decadent west. Zhivkova’s scholarly path was, however, cut short, when her mother died in 1971. Zhivkova then took on the role of de facto First Lady of Bulgaria, which exposed the 19-year-old to the inner workings and protocols of statecraft, and signalled the start of what turned out to be a rapid rise through the Bulgarian Communist Party nomenclature.

However, Zhivkova’s rise almost came to an end on 12 November 1973 in an event that would have great repercussions on her worldview. It was common practice that the Politburo would ceremoniously wave off their leader from the airport when he’d be on his way on some official state visit. Bulgaria was no exception. Late in joining the official delegation at Sofia Airport to see off Todor Zhivkov on an official trip to Poland, Zhivkova—at that time the first deputy chair of the Committee for Art and Culture—was being driven in her government Mercedes at a speed of well over 100 kilometres per hour. While approaching the airport, an oncoming Moskvich car was overtaking a long truck but then crashed head-on into Zhivkova’s speeding Mercedes. Lyudmila Zhivkova sustained a severe brain injury in the accident and was lucky to have survived. But it was following this accident that Zhivkova, only 21 at the time, defied orthodox communist ideology and turned to alternative medicine and spirituality to heal her. Much to dismay of the Communist Party leadership, Zhivkova started seeing officially discredited healers and psychics, particularly the now world-famous fortune teller Baba Vanga, whose association with Lyudmila Zhivkova saw her not only become a popular celebrity but also an important government sage and advisor. Zhivkova also took up a great interest in traditional Indian mysticism and medicine, something that she would later weave into her cultural mission for Bulgaria. She too was a complete vegetarian, which was always at odds with official policy at the time, but combined with the effects of the Bulgarian economy’s stagnation on food production, she was perfectly positioned to encourage the benefits of vegetarianism. Up to then, vegetarianism in Bulgaria had been associated with fringe spiritual (and therefore banned) groups such as Peter Deunov’s Universal White Brotherhood, and so was seen as cultish and deviant behaviour (a belief that still persists with many in the Balkans). Zhivkova also always stuck to a strict diet, vigilant on never gaining a single gram over her 48 kilograms. Now had any rank-and-file Communist Party member been caught doing things like this, they would’ve been expelled from the party, but being daddy’s girl, Zhivkova had free rein.

By 1975, when Zhivkova become the chairperson of the Committee for Culture, effectively making her Bulgaria’s culture minister, she started receiving her first real death threats and was assigned security detail. One of her closest bodyguards, Dimitar Murdzhev, wrote a memoir of his time guarding Zhivkova, revealing plenty of insider details. Murdzhev recalls that Indian culture and mysticism dominated Zhivkova’s life; she would be constantly reading otherwise banned literature about yogis, gurus, meditation and ayurveda. What she learnt from these books then began to creep into her official speeches, such as replacing the clichéd ideological expression “communist upbringing” with “aesthetic upbringing”. Her statements came perilously close to being anti-party, which if anyone else had muttered would have seen them being banished from the system. All this irritated the older dyed-in-the-wool communists, most of whom had been guerilla fighters and activists along with Lyudmila’s parents. Bulgarian poet Lyubomir Levchev, considered to be Zhivkova’s deputy and very much was on the same wavelength as her, wrote in his memoirs that “every time Lyudmila replaced the word ‘revolution’ with ‘evolution’, the growl of the irritated Minotaur shot out from the caves of dogma”. But any opposition within Bulgaria’s then-ruling Communist Party, even in its highest echelons, stood little chance of success without first gaining the Kremlin’s support. And in one instance, Zhivkova in her imprudence practically handed to the factions opposing her a trump card.

Unsurprisingly, Zhivkova made many trips to India. Travelling there could easily be presented as political given India’s (primarily military) alliance with the Eastern Bloc, and with Zhivkova having befriended then Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who had succeeded her father as head of the country, this was interpreted as a form of mentorship for Zhivkova’s own succession plans. But the main reason for these trips was Zhivkova furthering her knowledge in all things to do with Indian mysticism. Zhivkova met with many of luminaries of Indian mysticism, including the Russian artist Svetoslav Roerich, a long-time resident in India and the son of famous mystic artist Nicholas Roerich. Their friendship blossomed and Zhivkova became a strong advocate for him to the point that Zhivkova later declared 1978 in Bulgaria to be the Year of Roerich. Moscow, however, perceived this to be an anti-Soviet move as his Roerich’s father had been an anti-Communist White émigré. This for people who claim that the Kremlin was behind Zhivkova’s demise was proof enough that she was not to be trusted and had to be eliminated.

Todor Zhivkov was reported not to have liked his daughter's views or interests, and was deeply upset over her closeness to fortune tellers and faith healers such as Baba Vanga, but he was a Balkan dad after all, and with the loss of his wife and fellow comrade-in-arms, he certainly relied on his daughter a lot, so he protected her.

While Leonid Brezhnev was at the helm of the Soviet Union during the 1960s and 1970s, Todor Zhivkov’s unswerving loyalty to the USSR and to Brezhnev himself gave Zhivkov protection to ensure no opponent would ascend to any position that could challenge his power. But the guarantees of Brezhnev’s personal protection started to wane as his health started to deteriorate rapidly in the late 1970s. Zhivkova also sensed Soviet disapproval of her through a number of indirect signs and suspected that Soviet agents were spying on her.

As the effective head of culture in Bulgaria, Zhivkova allowed a partial thaw in ideological purity, granting Bulgaria’s artists relative freedom to pursue their true art. It’s mainly because of this that many in Bulgaria’s intellectual circles still laud Zhivkova. She also sought a greater role for Bulgaria on the international scene, politically and culturally, which primarily took on the form of worldwide exhibitions of ancient Thracian archeological discoveries (especially intricate gold art), and the promotion of Bulgarian traditional music and dance. The aim was to capture a sophisticated western audience and in doing so gain its approval. This served to overcome Bulgarian insecurities of being perceived as ‘backward’ and ‘uncivilised’ on account of not being ‘European’ enough after five centuries of Ottoman rule.

One of Zhivkova’s pet projects was the launching of a children’s festival in 1979 called ‘The Banner of Peace’, which brought children from around the world to Sofia. A propaganda triumph for Zhivkova, I recall the images in the magazines my grandfather would receive from Bulgaria at the time showing children drawing pictures with chalk on the streets of Sofia and wanting to be joining them. A special park with bells donated from these delegations can still be found in the southern outskirts of Sofia. Another pet project of hers was the lavish celebrations of 1300 year of Bulgarian statehood in 1981. Her father had received Soviet permission in 1979 to hold such a blatantly patriotic event, but then again the Eastern bloc had a thing for celebrating jubilee anniversaries like this. Very much whitewashing Bulgaria’s medieval past as a feudal kingdom in contrary to the teachings of communism, millions of leva were splurged on huge concerts and commemorations, mass participatory events and promotional materials, as well as statues and monuments, all espousing a sense of exceptionalism and that communist Bulgaria was the culmination of the country’s centuries-long struggles and battles for sovereignty. The biggest physical legacies of those celebrations were the opening of the spaceship-like and now internet-famous Buzludzha monument, as well as Sofia’s centrepiece National Palace of Culture (NDK), the giant theatre complex in the heart of the capital that was projected to be built in twelve years but completed in four. One monument from that time that no longer exists though was the much despised 1300 Years Bulgaria monument in the huge plaza in front of the NDK. Featuring abstract images of past historic figures to some of the little people who made up Bulgaria’s past, one of which was believed to resemble Todor Zhivkov. The city of Shumen in eastern Bulgaria became the the site of a huge monument also opened in 1981, ostensibly because it was the biggest city closest to where the first Bulgarian state was formed but also because the area had a large Turkish population that, let’s say, “needed a little reminding of who that area truly belonged to”.

- Clip of Lyudmila Zhivkova opening the Banner of Peace Monument

While many Bulgarians praise Zhivkova’s efforts for the affirmation of Bulgarian culture in Bulgaria and abroad, these displays served equally as a distraction. Promoting a rather heavily defined form of Bulgarian national identity, often at odds with the internationalism that “real socialism” (to use the official term employed to describe the systems in place in the Eastern bloc at the time) purports to encourage was a counter to Bulgaria’s slavish external support for the Soviet Union (even Bulgarians would joke that their country was the 16th republic of the USSR). The bread and circuses of the 1981 celebrations were also supposed to turn attention away from growing public dissatisfaction with the economic stagnation that had gripped Bulgaria at the time, but had an underlying opposite effect considering the “voluntary” contributions Bulgarians needed to make for the construction of the monuments like Buzludzha. This official use of Bulgarian nationalism as a distraction for the ethnic Bulgarian masses was at the detriment of Bulgaria’s ethnic, religious, linguistic and cultural minorities, continuing a strategy Todor Zhivkov had employed throughout his reign, reversing the lofty revolutionary policies of the first years of Bulgarian communism. Over the decades of Zhivkov’s rule, Bulgaria’s minorities had their individual identities curtailed one by one—first starting with the Roma, then the cancellation of Macedonian cultural autonomy in the late 1950s, the assimilation campaigns of the Bulgarian-speaking Pomak Muslim minority in the 1970s (resulting in armed resistance in one well-documented case) and culminating with the ‘Revival Process’ in the mid-1980s that saw Bulgaria’s Turks forced to change their names and being banned from speaking Turkish.

The success of the 1300 Years Bulgaria celebrations in 1981 was supposed to have cemented Zhivkova’s position as a true leader and a worthy successor to her father; however, it seemed to have had the opposite effect. That same year, the old guard of the Bulgarian Communist Party, made mainly up of guerilla fighter veterans of the anti-fascist resistance (Zhivkov’s immediate comrades), felt so emboldened to send a statement to Todor Zhivkov against his daughter, accusing her of deviation from Marxist-Leninist ideology, succumbing to mysticism and, worst of all to them, expanding cultural ties with the west. One of Zhivkova’s closest associates, Zhivko Popov, was also accused of abusing his position for profit. Zhivkova managed to prevent him being prosecuted by getting him appointed as Bulgarian ambassador to Czechoslovakia, but arrest and jail awaited him after his protection disappeared soon after Zhivkova’s death.

According to insiders, Zhivkova was fully prepared to battle the factions within the party elite who were against her. For over a year before her death, Zhivkova had been appealing to her father for them to have a serious talk about the matter, but her father kept postponing this. Zhivkova’s second husband, the infamous Ivan Slavkov, the former head of Bulgarian TV and who for decades after his wife’s death was the head of Bulgarian Olympic Committee (yes, completely corrupt), claimed that Zhivkova had the plans in place for the party old guard to be purged in late 1981.

However, this purge was never to be. What appeared to come out of nowhere, Zhivkova’s health deteriorated sharply after fainting during one of her visits to India. Then later in Mexico, Zhivkova was so ill that the entire trip had to be cancelled and a special government plane was sent from Bulgaria to bring her home.

No-one has said what exactly Zhivkova had been suffering from, which just adds to the suspicions, but many people close to Zhivkova, including famed Bulgarian Thraciologist and the then Bulgarian education minister Alexander Fol, at the time have claimed they witnessed that starting from the end of May 1981, Zhivkova had “given into her fate”.

The then head of the Union of Bulgarian Writers and hunting pal of Todor Zhivkov, Lyubomir Levchev claimed that a maid told him Lyudmila's turquoise ring turned white shortly before her death. Legend has it that turquoise has been known since antiquity to have the property to predict death: it turns white when its owner begins to swallow poison. However, it should be noted that such folksy anecdotes feature prominently in Bulgarian legends, ancient and modern.

Lyudmila Zhivkova’s final days saw her being increasingly absent from work. To the surprise of many of her associates, Zhivkova no longer was against mainstream medicine and in early July consented to go to the ski resort of Borovets for treatment, where she confined herself to her room for days. At the same time, it is said that Zhivkova’s archives and tape recordings, including the many conversations she had with Baba Vanga, were being destroyed.

According to her bodyguard Murdzhev, on the day of Lyudmila’s death, her father Todor Zhivkov invited her to have lunch together, which she at first refused but quickly after she changed her mind and ordered Murdzhev to take her to the presidential residence in Boyana. When they arrived at the residence, Zhivkova ordered him to go to the hospital reserved for the Bulgarian Communist Party elite to get two medicines for her. Murdzhev brought them to her, she then told him to leave and he went to his post. Later at around 6 pm, he heard a scream:

“The maid was screaming in front of the bathroom. We went in and… we were speechless: Lyudmila Zhivkova's body was floating in the tub. We pulled her out onto the tiled floor. I checked her pulse at several places on her body. She was dead.”

Much is speculated that this was suicide, with many vague and contradictory accounts on the record of what happened between then and when the announcement was made on Bulgarian radio of her death the following day. Why did it take it so long for a doctor to appear at the scene of the death? Was the ambulance really delayed because of a flat tyre? Why did it take medical professionals 8 hours to confirm that Lyudmila was dead? Was it suicide or was this a cover after a hit job ordered by the Kremlin, the party old guard or a rival seeking to become Zhivkov’s successor? One of the biggest questions is why didn’t the much-vaunted clairvoyant Baba Vanga warn Zhivkova’s closest associates about her imminent death? Baba Vanga apparently told Levchev that she hadn’t been given any signs from the spirits that Zhivkova was in danger, but following that, Bulgaria’s feared State Security apparently warned both Levchev and Vanga not to spread “ambiguities”.

Officially, the state medical committee chaired by Zhivkova’s uncle, Prof. Atanas Maleev, stated that she died of a cerebral haemorrhage after having had severe and irreversible respiratory and circulatory disorders—in other words, a stroke. However, many Bulgarians still don’t believe that was the true cause, no matter how legitimate it does sound, which says more about the general treatment of the “truth” in the Balkans.

One theory people who insist that Zhivkova’s death was actually suicide and then covered up is based on the tenets of communist propaganda, where communists commit suicide only so as not to fall alive into the hands of the enemy or, in the negative, when they’re overcome with guilt for having betrayed the proletariat when discovered for being double agents, for instance. Otherwise, communists are “filled with optimism for a bright shining future”. Suicide would imply that Zhivkova did not believe in the tomorrow on which the regime pinned all its hopes, and if the leader’s daughter could not believe in this, then what example would that provide for the millions that formed the Bulgarian working class? That’s why the authorities would never admit to Zhivkova’s death being suicide. Likewise would they never claim that Zhivkova had been killed by special agents—such treachery was painted as only a capitalist thing.

With Lyudmila Zhivkova eliminated, her opponents in the party hierarchy gained the upper hand, leading to the swift purge, demotion and event arrest of many of her associates and protégés. Numerous buildings and cultural and educational institutions were quickly renamed after her, including the National Palace of Culture, but many of her books about “rounded personalities” and “imbuing public life with beauty” that contravene Marxist-Leninist dogma were quietly removed from circulation.

What has been Zhivkova’s legacy? Mixed, it appears. For many Bulgarians, she’s still revered as a tireless promotor of Bulgarian culture and national identity. For others, they see her a power-hungry, spoilt and out-of-touch child very much a product of the despised red bourgeoisie. Her living legacy has been her fashion-designer daughter Evgenia, who has maintained a high profile since the fall of communism and has often defended her mother’s legacy, and her outspoken son Todor Slavkov, who out of his many exploits, was the winner of Bulgarian Celebrity Big Brother in 2014. Their lives and tribulations have been constant fodder for Bulgaria’s tabloid press. You could consider them to be Bulgaria’s answer to the Kennedys.

Had Lyudmila Zhivkova succeeded in replacing her trademark turban for a theoretical crown, would communist Bulgaria have changed much or at all? Well, clichéd to say but we’ll never know. But what can be said that despite the appearance of a cultural opening during her reign as chair of the Culture Committee after decades of Bulgaria being in a rigid cultural straightjacket, it’s safe to say that it was just a veneer. Her promotion of Bulgarian patriotism verging on nationalism though culture soon after paved the way for greater repressions in Bulgaria, the repercussions of which have yet to be properly rectified. Never did Zhivkova truly challenge the political nature of Communist Party rule, so it’s highly unlikely that she would have changed the system. If there is one legacy of her time that still permeates Bulgarian society, it’s that much of what constitutes the narrowly defined physical characteristics of what many Bulgarians attribute to their national identity fully ripened under her tutelage.

In writing about the contradictions of Lyudmila Zhivkova, academic Ivanka Nedeva Atanasova wrote: “Because of its heavy emphasis on national identity, Zhivkova’s cultural politics reveal clearly several sets of contradictory components of the Bulgarian national character and in some cases challenge the conventional wisdoms about Bulgarians. These sets are the quest for cultural achievements versus limited state resources; excessive national pride versus ‘shameful national identity’; Russophobes versus Russophiles; East versus West or how to escape the geopolitical trap; and mysticism versus atheism.”

44 years after her death and Zhivkova still captures the imagination of Bulgarians to the point that it’s hard to believe that she hasn’t been alive for over four decades. Perhaps Zhivkova sought immortality through the pursuit of mysticism, but the mystique surrounding her, whether in life or in death, has what brought her true immortality.

STOP PRESS: As I’ve been writing this, the Bulgarian media has announced that Lyudmila Zhivkova’s son, Todor, died of suicide on 21 July 2025, exactly 44 years after the death of his mother.

.%20A%20day%20of%20campaigning%20%E2%99%80%20%E2%80%A6%20or%20a%20day%20to%20buy%20flowers%20%F0%9F%92%90.jpg)