Eurovision: 'the voting is all political and just for your neighbour'

This is a regular Eurovision complaint not only among Brits but also people in ex-Yugoslavia.

But wait ✋

Aren't the Balkan countries the biggest culprits of 'political' and 'neighbourly' voting at Eurovision?

Well, yes, Balkan countries, particularly ex-Yugoslavia, do vote for their neighbours... but definitely not for political reasons. Actually, if politics did come into it, then Balkan countries would be demanding minus points for their neighbours as punishment and reparations for all the perceived injustices they've caused to their innocent country.

So why then do we expect to see all of the ex-Yugoslav countries giving their 'douze points' among each other?

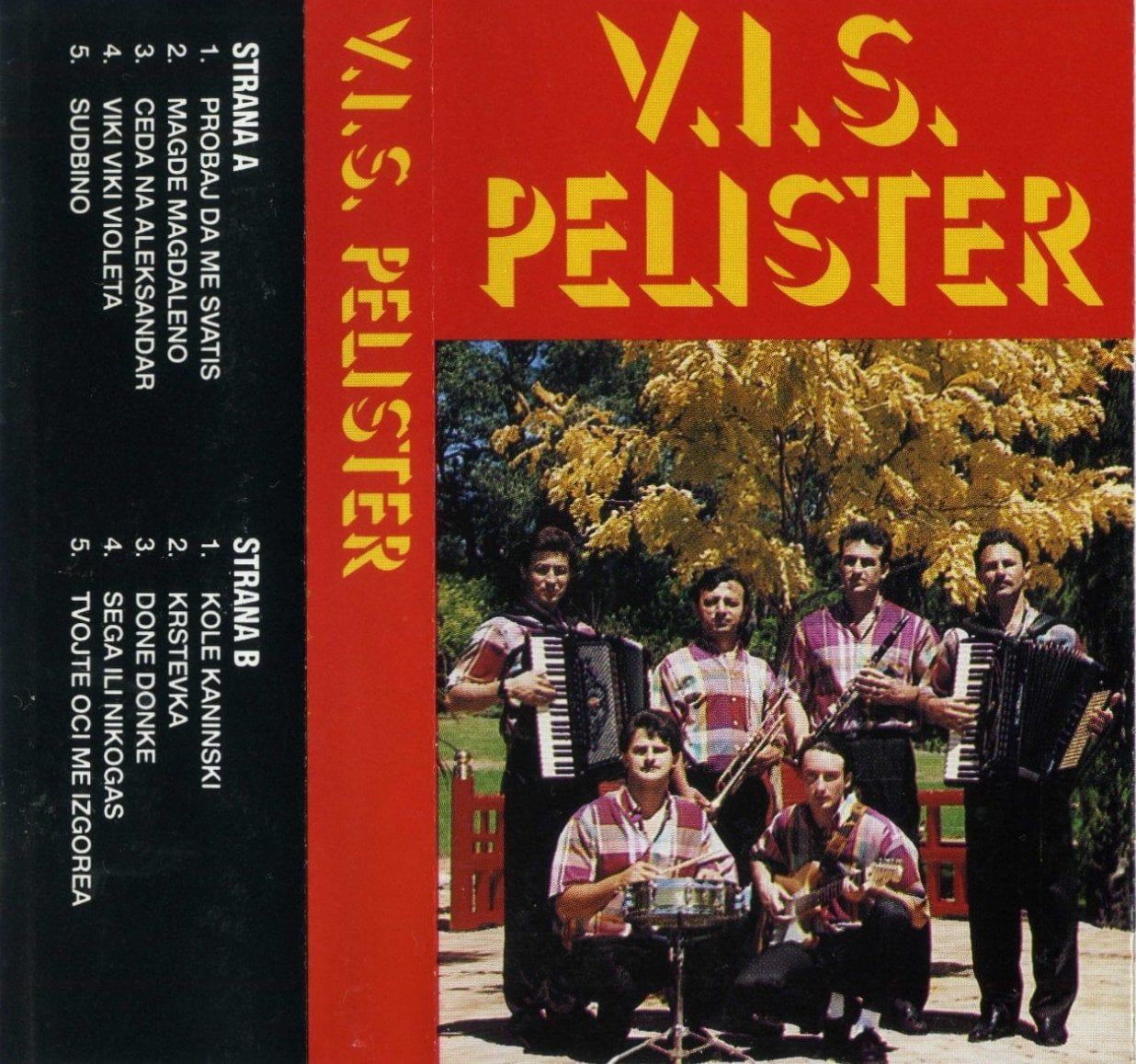

The primary reason is that while Yugoslavia has not existed as a country for over 30 years, thanks to its legacy of a shared national language (what was 'Serbo-Croatian') and pop culture, we still have a cultural 'Yugosphere'. This means that the biggest pop stars in, for example, Serbia, are usually also just as popular in every other ex-Yugoslav country. Likewise, there is then also major interest amongst the ex-Yugoslav countries as to who they will be sending to Eurovision. Sending a big-name act then almost guarantees big points from the neighbours iz regije ("from the region"), to use the euphemism employed locally to describe the now collective of countries that once formed Yugoslavia.

Let's take Serbia's 2022 entry Konstrakta, who was the only ex-Yugoslav act to qualify for the Eurovision finale that year. Her song In corpore sano ostensibly about an ill artist not entitled to national health insurance all while Konstrakta washes her hands onstage while pondering what could be the secret to Meghan Markle's healthy hair (it's Eurovision, after all), but also perceived to be a metaphor about political patronage and connections, an unfortunate but dogged aspect of Balkan life, was a phenomenon not only in Serbia but all of ex-Yugoslavia. Even the Croatian tabloids, which usually don't have a kind thing to say about archenemy Serbia, had been following Konstrakta's every move in the months leading up to Eurovision that year. With such blanket coverage and widespread regional acclaim for the song and artist, it was no shock when Serbia received top points from all the televotes of every ex-Yugoslav country participating that year.

What was a shock for pretty much everyone "in the region" was when in 2004, when Serbia and Montenegro (as the short-lived, renamed post-Federal Republic of Yugoslavia union) returned to Eurovision after being in sanctions wilderness for 13 years, received an unexpected 12 points from the Croatian public (100% televote then, no juries) for Željko Joksimović's classic Eurovision song Lane moje. This was a defining moment signalling that the war was definitely over and the Yugosphere was back. That didn't mean that the Croats and Serbs were back to being best buddies... far from it! But it showed that after 15 years of political and cultural animosity fueled by constant negative propaganda about the other side, the common cultural and linguistic traits that unite both sides won out. There was hope!

What also made Croatia's 12 points a surprise was that Croatian TV and radio had since independence in 1991 placed a semi-official blanket ban on broadcasting Serb and, when the Croats were fighting against them in 1992-4, Bosniak performers. One bureaucratic way to implement this was the editorial guideline that only songs sung in the 'ijekavski' form of what was Serbo-Croatian ('ije' being the main vowel basis that differentiates standard Croatian, Bosnian and Montenegrin from standard Serbian) be allowed to be broadcast on Croatian airwaves, thereby excluding most Serb performers who use the standard Serbian 'ekavski' form. However, Serbian as spoken to the west of the Drina river is also in the '-ijekavski' form, so ethnic Serb performers from Bosnia or Croatia, such as Zdravko Čolić and Neda Ukraden, who sung in ijekavski and were hugely popular nationwide in the final decades of Yugoslavia were too banned from Croatian TV and radio in the 1990s for having sought sanctuary in enemy Serbia. However, these ijekavski-singing Serb singers were among the first to be cautiously allowed back to Croatia during the cultural thaw post-2000. What these surprise 12 points from Croatia in 2004 ushered is opening the post-independence Croatian cultural sphere to most Serb singers and musicians, regardless whether they sing in ijekavski or ekavski, though mainly in the form of concerts and appearances – ekavski songs are still rarely shown on Croatian TV or radio stations (though not banned as before; songs in ekavski by the late Đorđe Balašević and the 1980s Belgrade new wave ska band Idoli appear on CMC, the main Croatian music TV channel), but Serb singers with tainted reputations (Ceca being top of the list) are still very much not welcome in Croatia.

The cultural Yugosphere is very much alive and well thanks primarily to the availability of satellite and cable TV and radio stations aimed specifically at the region as a whole. For instance, MTV started its own specialised station aimed at ex-Yugoslavia in 2005, though using any reference to 'Yugoslavia' in its name could've caused offence and even blocking by some authorities, so it opted to call itself 'MTV Adria'. There have been high-rating, pan-Yugoslav singing competition and reality TV shows: Operacija Trijumf in 2008, seasons 4 and 5 of Veliki Brat (Big Brother) and even a Survivor Serbia/Croatia. The most-watched TV show in ex-Yugoslavia in the past two decades, the Belgrade-based turbo folk singing competition show Zvezde Granda, features contestants from all former Yugoslav republics, with most of its winners of late being Bosniaks. The result of this has seen Serb singers doing phenomenally well in Croatia. For instance, Croatian-born Serb turbo folk superstar, and Lepa Brena's daughter-in-law, Aleksandra Prijović, holds the record for selling out Arena Zagreb (with a capacity of 23,000) five nights in a row in 2023, a feat no Croat singer has come close to matching, provoking wide debate in Croatia about popular culture in the country.

For extra proof of extra-national cultural spheres such as the 'Yugosphere', the 'Sovietsphere' and the one covering Spanish-speaking countries, check out this site mapping the number one YouTube songs worldwide in March 2021.

So when you see Montenegro, Croatia, Slovenia and Serbia (no Bosnia and Herzegovina or Macedonia this year to give points), don't scoff or boo. Be glad that the Eurovision cliché of 'music bringing people together' is actually happening here!

.%20A%20day%20of%20campaigning%20%E2%99%80%20%E2%80%A6%20or%20a%20day%20to%20buy%20flowers%20%F0%9F%92%90.jpg)