“When we retire, we’re going back to the village”.

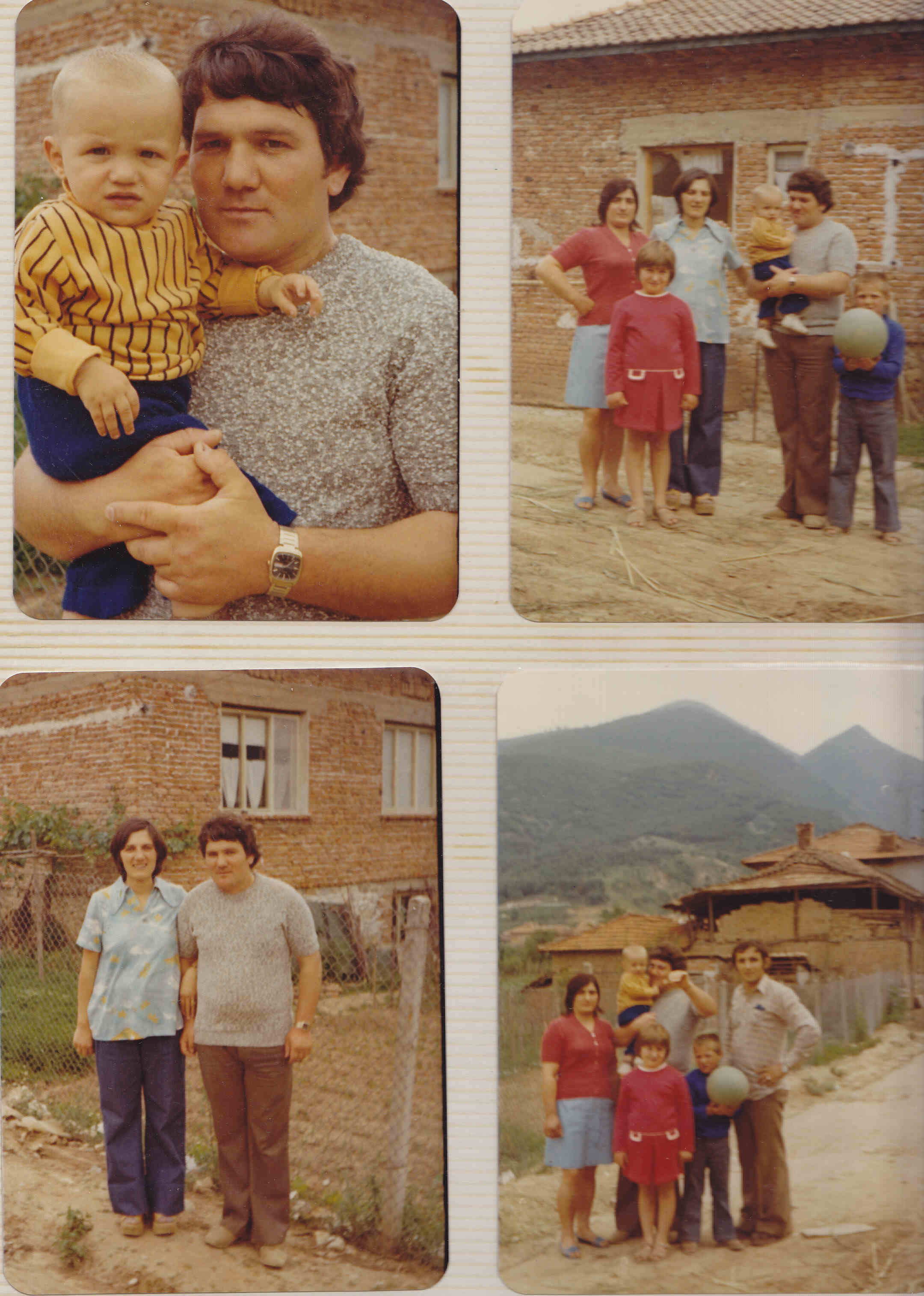

The dream of many a migrant, including my father, who in the 1970s had left Yugoslavia for some adventure and ‘become a cowboy like John Wayne’ in faraway Australia. Oh, was he disappointed once he stepped off the boat and choo-choo. Sorry but he wasn’t going to become a cowboy (or Australia’s equivalent, a jackaroo) as he dreamed.

More than 50 years later, our wannabe John Wayne has a very comfy life as a retiree in Australia, sans much yeeha these days. Doctor’s visits, jigsaw puzzles and watching Turkish soap operas dubbed into Macedonian on satellite TV is as exciting as it gets. Not the retirement he envisaged but more of an acceptance of reality. No matter what, it was no going back to live in the village of his birth, now a mere shadow of what it was. Even visiting stari kraj (‘the old place’) and the house where he grew up in, gone ever since my grandparents passed away, is just too arduous. Well, the 24 hours to get there and the jet lag only get worse as we age.

As a translator who works with Balkan Slavic languages, I often travel to the countries where these languages are spoken. In the summer of 2024, I was in the eastern reaches of Serbia – average temperature: 38 degrees Celsius. I had some free time, so in a last-minute decision (the best types,) I decided I'd head off to the point where Serbia, Bulgaria and Romania meet. That’s how I roll. To get there, I had to turn off the main road from the town of Negotin to the Bulgarian border and go down a heavily pot-holed path dangerous even for Balkan standards, to the final village before the border. But when I arrived in this village on the edge of nowhere, I immediately noticed two things.

The first was...

The houses in this village are beyond huge. I mean, they could be seen from space!

Now, I've seen mega-mansions such as the ones throughout Romania and in Soroca, Moldova, built and owned by their Roma populations, but this was not a Roma village. The houses were not as gaudy (OK, some are) but they’re just as large, with the biggest ones having up to 30 (!!!) bedrooms and are as high as five storeys!

The other thing I noticed about this village was...

It was almost devoid of people!!!

Had the raptures happened and I’d been saved? Very unlikely, but it sure did seem that way.

Missing were the aspects that make a Balkan village lively: the old men sitting around drinking rakija (grape brandy) and talking politics, a battered tractor or Yugo (the car) passing by or having to make way for stray chickens. No, none of that. There weren’t even evident shops or services. Truly a case of ‘last one out, turn off the lights!’

Eventually, I spotted some signs of life – mainly old people sitting in their yards. They’ve been left to look after these monstrous buildings.

But where, then, are the owners or would-be residents of these houses?

As could be seen from the car plates of the few cars in the village, Vienna mainly, but in general outside Serbia.

These huge houses are usually occupied only briefly in any given year. They are, however, testimony of a few things: the concept of belonging, return (but ultimately never happening), nostalgia, displaying "success" and stubborn one-upmanship.

While these concepts and their physical manifestation as the ancestral hearth ("ognjište" in Serbian) are very much a product of not just the of migration experience in Balkans but also worldwide, the extent that this was on display in this village was at a level I've never seen before.

But this village was not unique… the further I travelled around the region, the more near-empty villages with huge houses I found.

To give an idea of what these villages look like, here’s a ride through one…

So why have such houses, if hardly anyone is living in them?

These buildings are known as 'gastarbajterske kuće' (‘gastarbeiter homes’), mostly owned and financed by people who left these poor villages in the 1960s and 1970s to go work in western European countries desperate for low-skilled workers. As the name suggests, they were ‘guest workers’, i.e. temporary residents, who were to go back to their homelands once they were no longer working or needed. There was no chance for them or their children to gain citizenship of their host countries.

This was not one-sided though; official Yugoslav discourse at the time constantly emphasised that these workers were ‘temporarily working and living abroad’, something by the 1990s became an ironic euphemism considering many of them had been ‘temporarily’ out of their home countries for decades. In such an environment where the Gastarbeiter were made quite clear that they were and will always be outsiders, investing in a place to return was not only a practicality but also a much needed incentive for these workers to persevere with the harsh conditions they endured.

However, circumstances have much changed. Western European countries have since overhauled citizenship requirements, ensuring most are now no longer Gastarbeiter but Bürger (citizens), with children and grandchildren born, raised and educated in the ‘new country’ and who don't share that same belonging to the ancestral country as their elders.

So… why are these empty house so big?

The longer the original owners are away from the village, the bigger the extended family becomes. At first, the need was to accommodate only the immediate family, and for many in such villages in the 1950s to 1980s, having three or more children was quite common. Upon becoming adults, most of them would leave the village for greener pastures. Then they would have children, so more bedrooms were added for when they’d all come to visit the grandparents left behind. And then the grandchildren would grow up, get married and have children… requiring more bedrooms.

With families being widely dispersed, often across Europe and beyond, the ancestral home becomes the centrepiece and meeting point for family gatherings and celebrations such as weddings or major religious holidays, or in August when most of urban Europe shutters up for the month and heads off on holiday and/to where they came from. This common holiday period often becomes the one time of the year where families and former neighbourhoods can reunite and breathe life back to these villages. That means people are there in the high-life and carefree nature that comes with a holiday, so visiting the village ends up usually being a positive experience. Not having to face the actual harsh realities of living there only adds to the false sense of nostalgia for these villages.

A newer factor is greater accessibility. In the 20th Century, poor roads, relatively low car ownership, long and delayed bus and train trips, and prohibitively expensive airfares, alongside most Gastarbeiter not earning much, made any trip to the home village a costly and time-consuming undertaking – but a special event, nonetheless. Recent decades though have seen Gastarbeiter earning more, and driving better and bigger cars down modern motorways through control-free borders… until arriving at a thud to the bottlenecks that are the border points on the edge of the Schengen zone, most notorious of which is Horgoš on the border between Hungary and Serbia. The biggest change has been low-cost carriers, ferrying people from numerous western European airports at a fraction of the cost than before. The result overall is that people can, and do, visit more often.

But there are also more superficial and less dignified factors at play that have made these houses become the monstrosities they are now.

Villages have always been hotbeds of gossip, judgement, pride and prejudice. On top of that is the expectation for people who’ve left the village to show how successful their move has been. And what better way to demonstrate this than having a bigger house than your neighbours? Bring in a huge amount of inat, that quintessential Balkan trait of illogical stubbornness, the one-upmanship bursts out of the genie bottle:

“Dragan thinks he’s so much better than everyone else because his house has four storeys. Well, I’ll show him! My house will have five storeys!”

The outcome…

Ever bigger houses. More bedrooms. More garages. More ostentatious furnishings. More more!

While these villages may no longer be permanently populated physically, communities continue to live virtually on social media networks, particularly on village- or region-based Facebook groups, connecting former residents worldwide and replacing the local village square as the place for the latest hot news, complete with pictures.

Now, I know you’re probably wondering…

Who’s paying for all this?

I mean, building a big house requires a big budget, and since houses of this magnitude, and taste, in the countries where these migrants live and work are often associated with being in the domain of people engaged in, let’s say, less-than-legal enterprises, then surely that’s what’s happening here too (as has been heavily speculated on the net)?

Well, yes, there’ll always be those types, but the overwhelming majority of the owners of these houses are your average people working manual jobs, often pulling long shifts while living frugally in cramped, rented flats in the outskirts of depressed industrial cities.

Not talked about though is the massive environmental impact the construction and maintenance of these mega-mansions have. The Balkans are not that great when it comes to environmental matters, particularly waste disposal; my grandfather would fill his wheelbarrow with the household waste and chuck it all into the river. That explains why so many parts of the Balkans have plastic bags and waste strewn all over the place. Construction comes with massive waste, whether it be excess concrete, broken tiles, empty paint cans, used packaging… you name it. So it’s sad to see what once were fertile fields on the outskirts of villages are now rubbish dumps with vast piles of construction waste, like this…

One of the many reasons why I'm fascinated by this whole phenomenon is this: the house in Macedonia next door to the house my father grew up in watching cowboy films, is also a mega-mansion. The family lived in Vienna (there it is again) and the mother and father were putting in long shifts doing manual work to pay for building their dream house “back home”. They had the same plan as everyone else: when the time comes, they and their children and grandchildren will go back to live in the village. But when the father finally retired, even the mother, let alone their Austrian-born and raised children and grandchildren, who can hardly speak Macedonian, had no interest in leaving their nicely established lives in Vienna.

Not willing to give up on his prime investment and dream, the husband turned his back on his family and returned to live in the huge house on his own. The nerve! Tongues in the village couldn’t stop wagging over this scandalous act. You see, even the villagers couldn’t understand why he would want to come back to the village when he could live in, to use the term that they use, a ‘normal country’ like Austria, with a functioning healthcare and welfare system with clean streets and no visible petty corruption. Our neighbour didn't last long though. He unfortunately died a couple of years later from self-neglect and loneliness, and left behind what once was an impressive building painted in baby blue but now is a ruin that no one wants.

- Singing the Balkan blues. Serbian folk singer Zorica Marković with her lament about living in Austria.

While these houses once represented a focal point for families to reunite, they are now places which cause separation and even irreconcilable family fights. I once met a Kosovar Albanian woman in London who had lived in the UK most of her life (no, not Dua Lipa or Rita Ora), married to a Brit and expecting her first child. Quite often Albanians and Slavs don’t see eye to eye, but coming from Balkan emigrant families meant we had so much in shared experiences. She told me how her parents were about to retire and eagerly waiting to move back to Kosovo. Yes, that plan! I asked her will they want to be living there on their own away from their grandchild? How will she cope not having gjyshja (“grandmother” in Albanian) to provide babysitting on call? Also, would her parents be able to deal with the threadbare Kosovan health system and life-crushing bureaucracy? She said that's something she's been warning them but who’s to listen?

Many people who idealise this retirement in their place of birth only realise too late how different they’ve become having lived and worked in their adopted countries, having acquired different expectations of what is considered acceptable behaviour and practices at odds with their old-but-new compatriots. The logistics and reality often eventually outweigh the dream.

The biggest question is this: if no one is living in these houses and are unlikely ever to be fully occupied, then what will become of these houses in the future? Often the children and grandchildren of the owners of these buildings have never lived in Serbia and their only experiences of the village were initially ( as children) joyous – a place for summer holidays or family gatherings – with the safety of the village providing opportunities for frolics unavailable back ‘home’. But that excitement often turns to boredom, entrapment and uncoolness as they become older. They'd prefer to go on holiday to the same places as their western European friends; some place fun like Majorca or Crete instead. Later, as adults who have lived all their lives in cities in Western Europe, there’s no interest in wanting to uproot everything and ‘return’ to a village with no people in a country that is practically foreign to them.

For the owners of these empty houses, trying their luck to recoup their losses by selling these palaces is futile – no one is interested in buying. So the future looks bleak – undoubtedly these villages will remain as ghost towns, not unlike those that were once the settings in the cowboy films my father used to watch.

There is, however, one section of these villages is experiencing a boom in numbers… the cemetery. If the original inhabitants don’t end up retiring in the village as planned, then there’s a greater will to be buried there and be with the rest of the ancestors. But as in life, so too in death: mirroring the circumstances with their houses, going all out and outdoing the neighbours in that perpetual competition of one-upmanship is also taken to the grave. The final resting places for families are often huge crypts mimicking the style of the ghost houses the deceased once owned. And even though there have been funeral companies servicing the diaspora communities with the repatriation of corpses (I’ve had to translate a number of those documents), this too is starting to taper off as more of the emigrants opt to be buried in the ‘new country’ where they’d lived for most of their lives and where their descendants can tend to their graves.

A plus of sorts for these buildings is that it does provide employment opportunities in construction, sales and administration for many who decide to remain. However, as can be seen by the average age of those engaged in these industries in the Balkans, despite the amount of work available, why would, say, young plumbers want to stick around in a rural part of Balkans when they could earn much more and work in better conditions in a western European country.

Like the cowboy that my father wanted to be, these empty monuments to family, belonging and superficial wealth, ate my dust as I headed off into the Serbian sunset. Driving out of the village was once, and still often is, a painful goodbye for those who no longer live here. Today, these villages with their empty mega-mansions left me amazed at what lengths people would go to prove that they’ve ‘made it’, as well as the power of the need to have a physical centre of belonging. They say home is where the heart is, but do we need it to be bricks and mortar? Shouldn’t it transcend that, especially when the soul of these places has long gone. I wonder for all these people who busted their guts for these empty houses: was it really all worth it?

.%20A%20day%20of%20campaigning%20%E2%99%80%20%E2%80%A6%20or%20a%20day%20to%20buy%20flowers%20%F0%9F%92%90.jpg)