Bali, the popular tourist island in Indonesia, is the unlikely intro to a piece about Ethiopia and Yugoslavia, but trust me, there’s a link.

My Macedonian parents, one born in Australia, the other in then Yugoslavia, decided that they’ll join the Aussie conveyor-belt and go on their first trip there. You see, Bali for Aussies is like what the Costa del Sol is for Europeans – cheap mass tourism full of the drunken worst of their own lot. My parents don’t fit the Aussie stereotype in any way or look, and hadn’t been to any Asian destination before, so they opted it’d be best to get a local guide to show them around. Knowing from experience to make the small talk many westerners insist on doing, their guide asked them where they come from and they instinctively replied they’re from Australia… but the guide looked at them in disbelief. I mean, they wouldn’t have looked like any of the other Aussie tourists that this guide had dealt with before, and my father’s heavy Balkan accent and somewhat broken English are also major give-aways. Sensing the guide’s bewilderment, my mother then added “but we’re of Macedonian origin”. Nah, that didn’t work – the guide could not place this ethnicity in his head, so my father then added for clarity “Yugoslavia”. That was the password! The guide immediately lit up in awe and replied “Ah, Tito! He was good friends with our president Sukarno.” That’s right, Tito was very good friends with Indonesia’s first president, and together with other prominent anti-colonialist leaders (Nasser, Nehru, Nkrumah…) in 1961 formed the Non-Aligned Movement. That was it… having firmly established that my parents are of Yugoslav origin made them exalted guests to be afforded the type of hospitality that Tito himself would have received when visiting these countries.

Now one thing that many tourists complain about Bali, particularly in tourist-central Kuta is how unrelenting the touts are accosting tourists. Well, not for my parents. Their guide would say the magic word “Yugoslavia” to any chancer and, near-miraculously, my parents were able to go on in peace. It most remarkably happened to my parents when going through a crowded marketplace – their guide said something out loud in Balinese to the hawkers, my parents distinguished “Yugoslavia” and “Tito” amongst the words, and immediately the hawkers were in complete deference to them – it was as if my parents were Tito and his wife Jovanka themselves. Lap it up!

Such is the legacy of Tito, Yugoslavia and its peoples around the world – a level of utmost respect that has endured decades of massive worldwide political change… or perhaps more so in defiance of what has happened since.

This ongoing respect for Tito and, by extension, Yugoslavia, decades after the leader’s death and subsequent destruction of the federation he ruled, has always fascinated me. It’s of course still quite prevalent throughout ex-Yugoslavia and its diasporas as witnessed in social media. Tito’s tomb in Yugoslavia’s capital Belgrade (Kuća cveća i.e. the House of Flowers) is still impeccably maintained. There are still streets and monuments dedicated to Tito to be found not only throughout what was Yugoslavia but also worldwide. But to see that this still also happens outside of Yugoslavia to this date is simultaneously amazing and bittersweet – there’s pride that our not-so-perfect union of Southern Slavic nations truly punched above its weight on the world scene, accompanied by the subsequent sadness and frustration when looking at the dysfunctional nature of the statelets that have superseded Yugoslavia – we have lost so much and never would it be regained.

Still, based on my parents’ experience in Bali, I wanted to investigate how much of this legacy lingers in other countries, particularly those most closely allied to Yugoslavia.

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM), one of Tito’s prize projects, had the somewhat unexpected effect. Not only did it position Yugoslavia and Tito at a level to confront the two main Cold-War adversary blocs: the US and its allies in Western Europe and the USSR and its allies in Eastern Europe, it also rewardingly granted your average Yugoslav with a window to an otherwise inaccessible and exotic world. The latest about Tito’s journeys around the world on his luxury boat Galeb was daily headline news. Yugoslavs then were treated to a never-ending travelogue to places they didn’t even know existed. In turn, the African, Asian and Latin American leaders Tito would visit often became household names in Yugoslavia, and in certain cases the prompts for children’s names – for instance, “Indira”, after Indira Gandhi, was one of the most popular girl’s names in Yugoslavia from the 1960s to the 1980s. Particularly for the generations who grew up listening to radio reports of these travels, mention the names of these countries and the first response will be their respective leaders, just like how the Balinese guide said “Tito” once my parents mentioned “Yugoslavia”.

In many cases, their anti-colonialist hero leader, who would also be their first post-independence president, is the only thing people knew about that country. Take the case with the first country I tested in-person to see whether Tito and Yugoslavia mattered: Tanzania.

In 2019 when I said to my father that I was going to Tanzania, his first reaction was to say “Ah, Nyerere” i.e. Julius Nyerere, the “father of the Tanzanian nation”. Nyerere, like many of the stars of the Non-Aligned Movement, had much in common with Tito – an impeccable record as head of the country’s liberation movement, socialist ideology, cult of personality – so they were great allies. So when I was in Tanzania, I tested it out by randomly mentioning “Yugoslavia” here and there. The result? Sorry, no, hardly a response. Interestingly, I didn’t find Tanzanians, most of whom never lived during Nyerere’s rule, to be as interested in revering their first president as much as ex-Yugoslavs still do with Tito, or for that matter with other African contemporaries of Nyerere in their respective countries – compare this to neighbouring Kenya and the population’s reverence for Jomo Kenyatta. By extension, Tito and Yugoslavia didn’t hold any interest either, so mentioning to Tanzanians that their Nyerere was good friends with our Tito usually fell on deaf ears. Granted, I didn’t have much opportunity to talk to older Tanzanians, and sorry to say, Nyerere for Yugoslavs was not as prominent as the other big-hitters of the NAM.

Though I should add that I did have a Balkan encounter in Tanzania when Greg, an Australian friend of mine who was living in Dar-es-Salaam at the time introduced me to his architect colleague, Marina, who just happened to be Bulgarian. Her husband was Tamil Malaysian and their daughter, who was born in Sofia, was then attending a local school and spoke English, Swahili and Bulgarian. I asked Marina why of all places she ended up in Tanzania? Her response: to get as far from the Balkans as possible!

Nickipedia is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

OK, Tanzania turned out to be a fizzle for Tito, at least in my case. Maybe it’ll be different with Ethiopia, where an opportunity to visit came up for me in 2023.

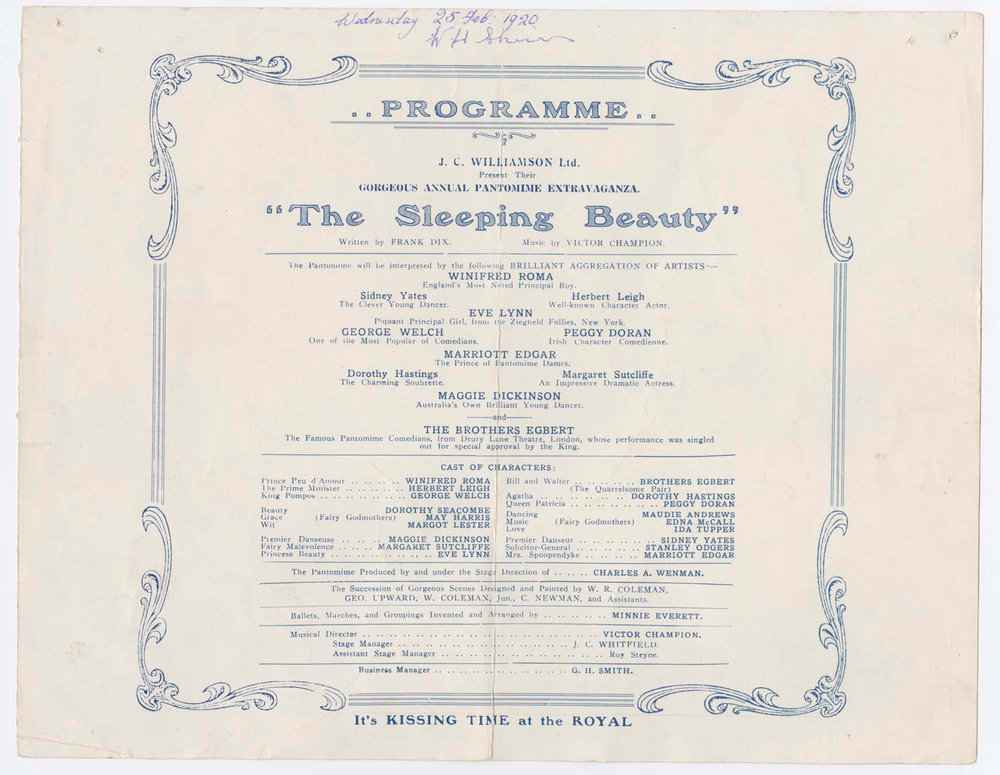

Before heading out, I tried the association test again with ex-Yugoslavs — I said “Ethiopia” and heard their immediate response. For people more my age, the primary association was YU Rock Misija – the Yugoslav answer to Bob Geldof’s Band Aid of 1984/1985. Yugoslavia too had its own celebrity charity song to raise funds for the starving in Ethiopia – Za milion godina (For a Million Years), featuring most of the big names of Yugoslav rock and pop at the time. YU Rock Misija also had its own Live Aid-affiliated concert in Belgrade’s Red Star Stadium on 15 June 1985, two days after the main event worldwide, with proceeds from the single and concert going to Band Aid. No neo-folk singers such as Yugoslavia’s biggest star at the time, Lepa Brena, were invited to attend, underpinning the very “urban” and “western” nature of it all. Also strikingly absent from the YU Rock Misija line-up were some of Yugoslavia’s biggest rock acts: Bijelo Dugme fronted by Goran Bregović; Sarajevo punk band Zabranjeno Pušenje (“No Smoking”), which during the 1990s Balkan wars split on ethnic lines, with the Belgrade-based (and therefore Serb) No Smoking Orchestra reforming under the leadership of (in)famous film director Emir Kusturica; legendary troubadour and later dissident commentator Đorđe Balašević; and Belgrade rock band Riblja Čorba, whose frontman Bora Đorđević at the time nurtured an anti-establishment image that later morphed into unabashed support for extreme Serbian nationalism. Đorđević claimed he did not want to be part of a “government-sponsored event”, but the reality was that YU Rock Misija was an independently organised project, more to show how much Yugoslavia was culturally part of the “west” rather than out of any genuine desire to help Ethiopians. In fact, Yugoslavia’s communist authorities deliberately downplayed the Ethiopian link to it all lest that it ruptured the otherwise good relations they had with Ethiopia’s then pro-communist Derg regime.

However, asking older ex-Yugoslavs about Ethiopia and the answer I received almost without fail harked back to a now-mythical time: “Haile Selassie”.

Haile Selassie I was Ethiopia’s emperor from 1930 until overthrown in a military coup in 1974 and murdered a year later. For many in the west, the only thing they know about Haile Selassie is that some Rastafarians worship him as God incarnate. But it wasn’t any link to Rastafarianism, reggae music or Bob Marley why older Yugoslavs know of him. Haile Selassie I had a very special relationship with Tito, one that is the stuff of legend, as I was to be reminded constantly.

It’s invaluable to get some insider advice for any destination. Luckily for me, I had the perfect person to ask about Ethiopia – Meredith, a US translator colleague of mine. Her pluckier younger self had first idealistically gone to Ethiopia with the Peace Corps, but what was supposed to be a six-month stint ended up being something more permanent. Meredith fell in love with a local Ethiopian man, they married and had two lovely children together. As a translator of Amharic into English, as well as an activist advocating greater recognition for African languages online, Meredith would regularly post on social media about everyday life in Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa, with a particular focus on the lives of its translators and other professionals. This rare perspective was what drew me to Meredith’s work. It was only the deterioration in the security situation in Ethiopia and the threat of the country’s three regional civil wars reaching the relative safety of Addis that prompted Meredith and her family to make the move to her home state of Pennsylvania, where they are now.

One of the questions I asked Meredith was whether Emperor Haile Selassie I is still revered in his former domain. I know from past experience, particularly in the Balkans, that it’s always best to be cautious when talking about past leaders, so I was wanting to avoid any possible unpleasantries if I unwittingly raised the name who’s considered unsavoury. For if Haile Selassie was not in favour, then so too won’t be Tito.

This is what Meredith said to me: “He’s very much made a comeback in the past decade and people really honour him. The current government sees him as a hero so you’ll see when you go to the museum a lot of artefacts and pictures.”

Good news, and as I went on to discover, completely spot on.

I flew into Addis Ababa on a red-eye from London on Ethiopian Airlines (service with so much heart!). Once settled in my hotel, I set up a meeting with a friend of a friend, Heruy, one of the many Ethiopians who had lived for some time in that other “Ethiopia” – Washington D.C., and now a music promoter. Our meeting point, a hangout for Ethiopian returnees from the United States and where English is the main language, was about an hour walk away. So I decided to forego the taxi and take to the streets – you see and feel so much more that way!

Off I went!

It didn’t take long for a tout to approach me. Not only with my fair features do I stand out, but because of the three wars happening in the country, most tourists were avoiding Ethiopia, and with many like Meredith in the foreigner community having left even the relative safety of the capital, foreigners in Addis were much rarer than before. That made the touts and grifters ever more focused to pounce on any foreigner come what may. But on the flipside, that also meant more opportunities for me to test how they react to foreigners drawing on the myriad of nationalities I can claim. It’s always an on-the-spot decision: do I tell them I’m Australian or British (rich) or instead go for Macedonian, Bulgarian or Serbian (poor). But my mission this time was investigating any Yugoslav connection, so that was my gameplan with the first Ethiopian I encountered on the streets of Addis Ababa…

- “Hey, my friend, where are you from?” says the tout to me.

- [With put-on Balkan accent] “I’m from Macedonia.”

- “Macedonia? Where’s that?”

- “You know Serbia? Yugoslavia?”

- “Yugoslavia?! Tito!!!”

BINGO! We have a winner!

And out it came. Gushing words of praise for Tito, who this Ethiopian constantly mentioned was a close friend of their great emperor Haile Selassie. Words can’t describe how overjoyed this Ethiopian guy was talking about this connection. As the conversation continued, this guy told me that his cousin even went to Yugoslavia to study at University of Belgrade in the early 1980s! Major respect. He wished me a wonderful stay in Ethiopia and let me go in peace. It was just like how it was for my parents in Bali.

This was just the start, for the longer I was in Ethiopia, most Ethiopians I met knew very well who was Tito and Yugoslavia, as if these entities still exist.

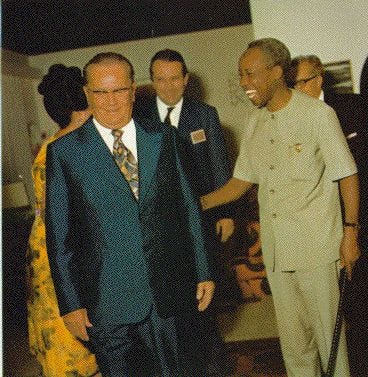

In 1954, Haile Selassie I was the first African leader to visit Yugoslavia, initiating what later became a number of mutual visits that by the 1960s had become near-annual events. Much regaled when I was in Addis Ababa was how in 1955 Tito stayed at Haile Selassie’s palace for a whole two weeks – an extraordinary display of hospitality bestowing great honour. These mutual state visits would see the two paramount leaders greeted by their subjects like the emperors they were.

Displays of Tito’s gifts to Haile Selassie I are on full display at in Ethiopia, such as these items at the Ethnographical Museum inside the grounds of the University of Addis Ababa.

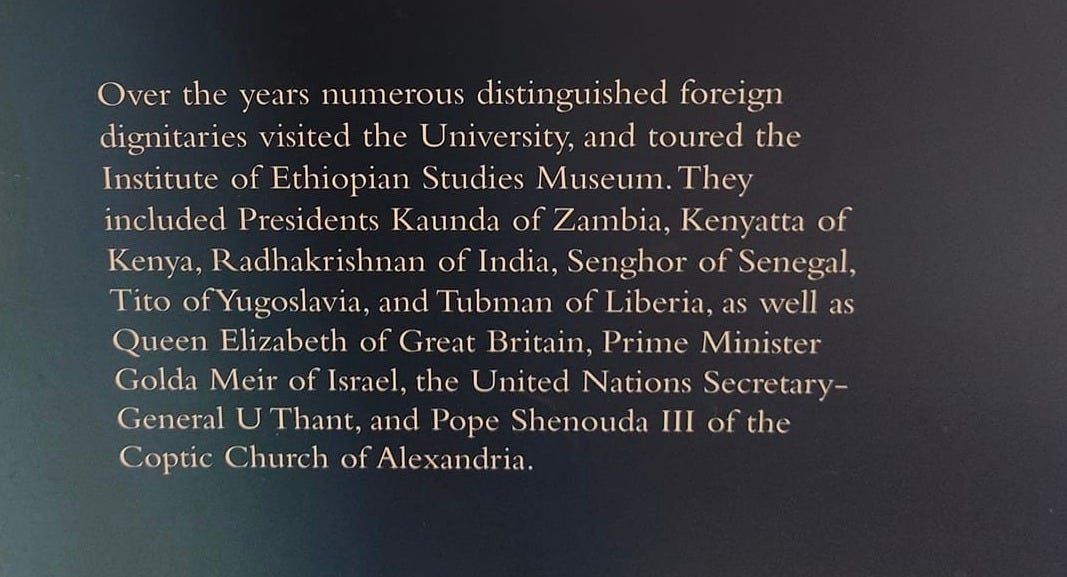

When I entered the ethnographical museum, a friendly employee asked me where I’m from. By this time, I just was saying “Yugoslavia”, and as expected by then, the greeting was jubilant. Of course his first response was “Tito”. He then showed me this caption on display telling how Tito had even visited the museum and was one of their most honoured guests ever.

Traces of Tito and Yugoslavia are easily found throughout Addis Ababa. Most significant is that one of the main streets in the centre of Ethiopia’s huge capital city is still officially called “Tito Street”; however, most younger Ethiopians have no idea that it’s even called that (there are no street signs). Of course, I had to go see it, and here it is…

OK, not as remarkable as I expected it to be. To be honest, it was a let-down.

Naturally, the impressive former Yugoslav (now Serbian) embassy is on this street. Though firmly hidden behind secure walls, the huge edifice set among sprawling grounds in a prime location in the centre of the Ethiopian capital is testimony of how important Yugoslavia was to Ethiopia. I was told, though, embassy staff were lamenting that the future of the building was under constant (and deliberate) threat, mainly on account of the site’s lucrative real-estate potential.

While it was possible to find out about the more obvious vestiges of Yugoslavia in Ethiopia, such as embassies and streets, beforehand, there was one significant Addis Ababa landmark that took me by major surprise.

While on the way out of Addis to the fascinating Debre Libanos monastery, dodging the lines of trucks transporting young soldiers brandishing Kalashnikovs, we passed the Yekatit 12 monument commemorating the victims of Italian fascist occupation and in particular those of the pogrom in 1937 that occurred on the date on the Ethiopian calendar after which the monument is named. What caught my eye with this monument was the aesthetics of its bronze reliefs – they seemed familiar to me. They weren’t Soviet. Nor were they obviously North Korean like at the Ethiopian-Cuban Friendship Park I had visited earlier. It somehow reminded me of the Pobjeda (Victory) monument in Batina, Croatia – one of the best examples of the socialist realism that characterised early socialist Yugoslav monumental art… and a genre Yugoslavs doggedly and yet mistakenly claim they did not espouse. Don’t tell me the Yekatit 12 monument is also Yugoslav? Well, my instinct was correct. As I was later told by the staff at the Ethnographic Museum, the monument (well, the bronze reliefs) was the work of none other than famed Yugoslav sculptor Antun Augustinčić, who as it happened to be, was also the author of the Pobjeda monument. Marshal Tito himself had presented these reliefs during his famed 1955 visit as a gift from the Yugoslav peoples to Ethiopia on the grounds that both countries had the shared bond of having been victims of Italian fascist oppression and violence.

However, things weren’t always so positive with Tito. One Ethiopian, a sassy woman and self-professed rock chick from way back, whose father had been a high-ranking official during the Selassie period and later evacuated his family to the United States, told me of the horror of experiencing the Red Terror years, when walking to school often involved her jumping over dead bodies lying on the street and pretending all was fine. She expressed the sentiment shared by many of her generation that Tito had massively betrayed Haile Selassie and their supposedly close friendship when Yugoslavia opted to provide full support for the new regime in an ultimately fruitless effort to prevent the Derg being swayed to ally with the USSR, which in 1977 initiated its own, ultimately successful, campaign to win over the new military Ethiopian government. With Ethiopia firmly within the Soviet orbit and following the Cuban path to civilian rule under a newly formed Eastern bloc-style Communist Party, Yugoslav-Ethiopian relations were downgraded. By the late 1980s, the Yugoslav public only heard Ethiopia being mentioned occasionally, such as when it was singled out as the main customer for Yugoslav armaments in the infamous Mamula Go Home article that appeared in the February 1988 edition of the critical youth Slovenian magazine Mladina, or that Ethiopia was the supposed film location for the video clip for Yugoslav superstar Lepa Brena’s 1990 hit Tamba Lamba (it was actually filmed in Kenya).

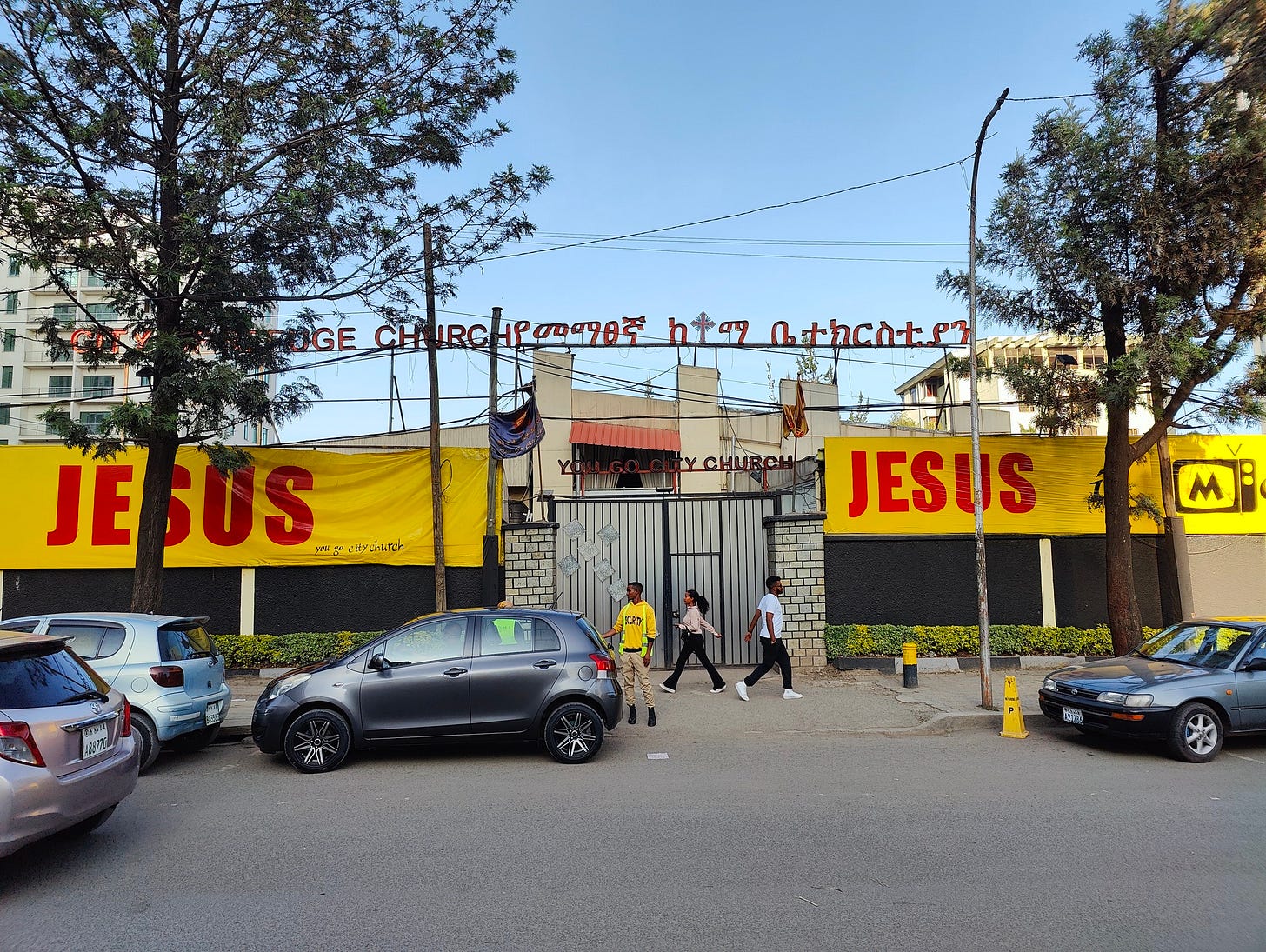

The fate of Ethiopia’s social history post-1990 though is mirrored, as I discovered unexpectedly, through the fortunes of none other than the premises of the famous Yugoslav Friendship Club in Addis Ababa, otherwise more popularly known as the “Yugo Club”. As was customary in socialist countries, to promote international solidarity with fraternal allies, friendship clubs were opened as venues for cultural exchanges; however, the fall of the Derg in 1991 saw many of these clubs shut up shop in Addis Ababa. The premises managed to buck the trend by living on to be site of one of the hottest nightclubs in Addis Ababa… known as the Yugo Club! Good thinking to keep the name! At least all the taxi drivers in Addis knew the address. The Yugo Club entertained the club kids of Addis for years, but like so many clubs in the ever-changing and fickle nightlife business, the Yugo Club eventually had its disco ball rotate for one last time and closed its doors. However, in a bizarre twist of fate, the place now lives on as a rather different type of venue. Ethiopia has seen the primacy of its own Orthodox Church challenged by a boom of evangelical Christian churches. New evangelical churches have popped up everywhere throughout Ethiopia, including at the former Yugo Club, going by the name – the You Go City Church. Get it?! Now I wonder what the atheist Tito would have thought about this?

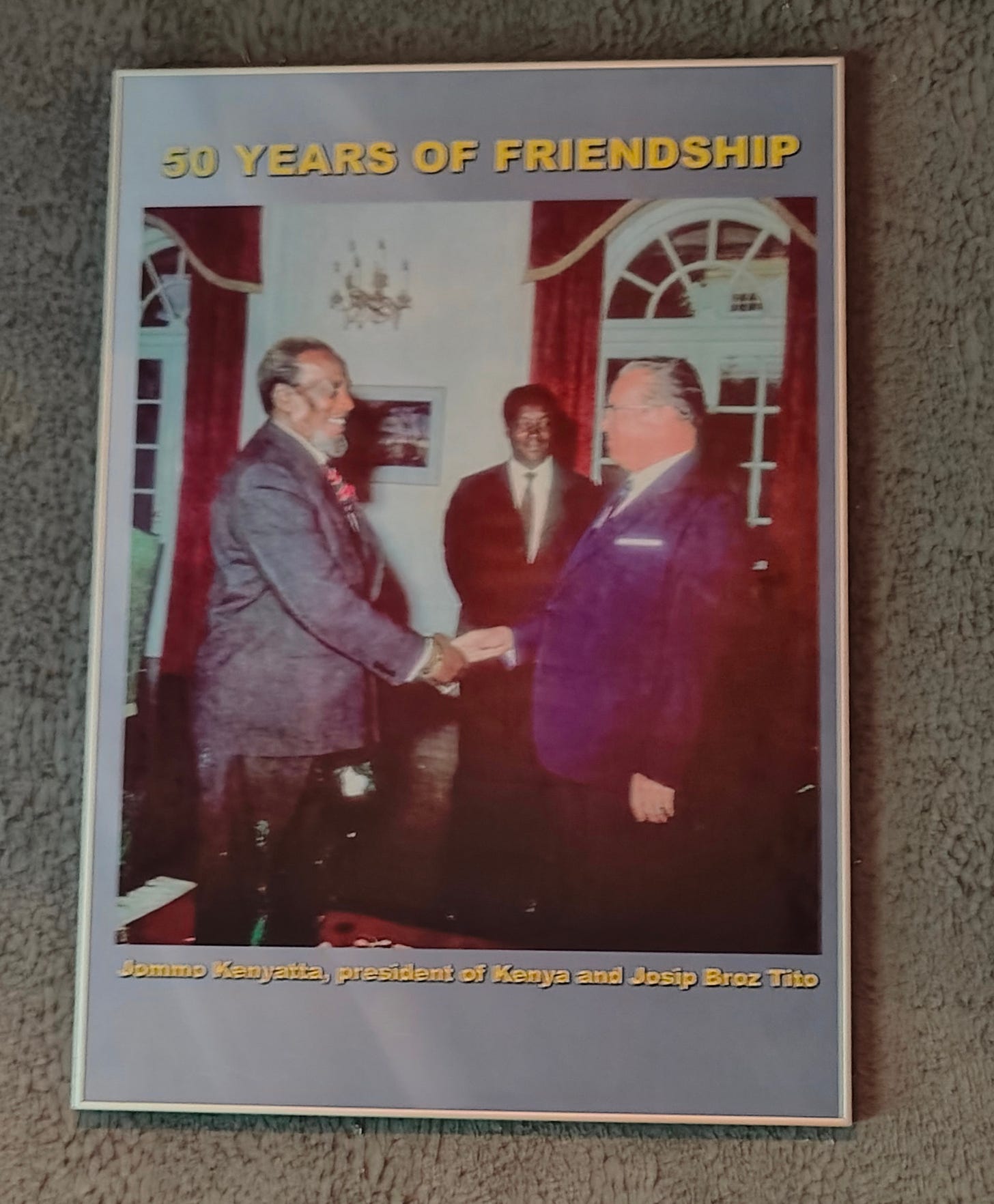

Yugoslavia’s successor states have also been able to capitalise of their parent country’s brilliant relations with NAM countries, particularly in Africa, for their own post-independence agendas. When India recognised Macedonia by its constitutional name over the temporary reference of “Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia” in 2008, personal relations stemming from the strong ties cultivated during the Yugoslav era were the key factor for pulling off this diplomatic coup, much to Greece’s anger. Likewise, Serbia has also exploited formal and informal diplomatic ties from Yugoslav times to ensure countries such as Ethiopia, Algeria, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe not recognise Kosovo as an independent state. And it’s with good reason that pride of place in the Balkan restaurant that I found by chance only the other week when I was in Nairobi is a giant picture of Tito with the Kenya’s founder Jomo Kenyatta.

Much is mocked at people in ex-Yugoslavia who pine for the days of Tito and Yugoslavia. Yugonostalgists are apparently dreamers at best and dreamers at worst. Yeah, sure, anyone can dredge up the less savoury aspects of Yugoslavia to make their point, and it’s a given that had things been far more grounded (and Tito anointed a proper successor), then the supposed brotherhood and unity of the “former country” (to use one of the many local euphemisms for “Yugoslavia”) would not have crumbled like it did. But what do the new successor statelets have to show for more than three decades of “independence”? Something that people around the world, let alone the Indonesians or the Ethiopian, have reason to gasp in awe whenever we say “Serbia”, “Croatia”, “Slovenia” etc.? No, it’s still “Yugoslavia” that gets them that way. What a legacy to have, and that’s despite the negative images of the wars that followed its demise, as well as poor governance. We who had the privilege of living during the time that Tito’s Yugoslavia existed have at least something tangible and present to be proud of… and have others look at us with so much respect that we can go through a crowded market and not be accosted.

And how did this respect all start?

By having the virtue to treat others as equals.

.%20A%20day%20of%20campaigning%20%E2%99%80%20%E2%80%A6%20or%20a%20day%20to%20buy%20flowers%20%F0%9F%92%90.jpg)