Here’s a fun, linguistic twist you may not know…

Recently, I came across two posts in professional translator groups asking a seemingly simple question:

How do you translate “cheese” into Macedonian or Bulgarian?

At first glance many reacted with complete disbelief: “Seriously? Isn’t it obvious? What a stupid question to ask!”

But actually it’s a perfectly valid query – and a great example of why translation is never as straightforward as it seems.

If we were to go by the dictionary, there is a generic term for “cheese” in both of these languages: in Macedonian it’s сирење (sirenje) and Bulgarian it’s сирене (sirene). This makes sense when looking at the word for “cheese” in other Slavonic languages where in all of them it is a cognate of “sir” (rhymes with “peer”).

However, as with so many everyday terms, practice suggests otherwise. This is the case with sirene/sirenje, for when you mention these terms to a Bulgarian- or Macedonian-speaker, the first and only thing they will have in mind is…

“white cheese” or “feta”.

Note though that not all white cheese/feta is the same – Greek feta is different from Macedonian feta, which is then different from Bulgarian feta.

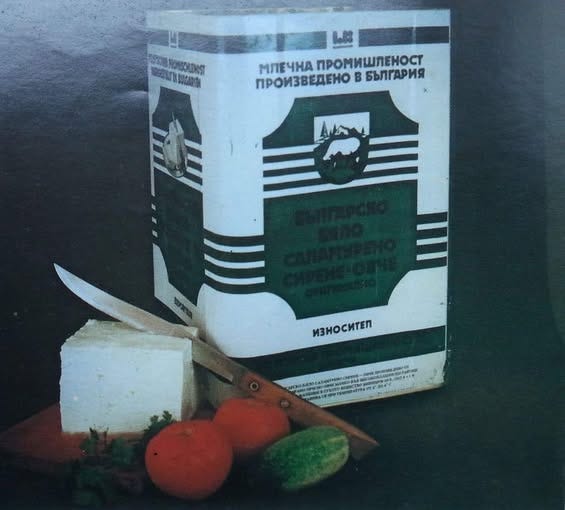

To be specific, what Bulgarians otherwise refer to as “sirene” is actually “white brine cheese” i.e. “бяло саламурено сирене” (byalo samalureno sirene). Go on – try saying that one! Yeah, no-one could ever say that this is perfect name for a product. For decades, this type of white cheese was one of Bulgaria’s primary food exports, usually marketed as “Bulgarian feta” and sold in its recognisable green-and-white (from sheep’s milk) and blue-and-white (from cow’s milk) packaging – something still done to this day. This cheese became one of THE symbols of Bulgaria. After Greece achieved gaining PDO status for their own “feta” (since upheld on appeal), “Bulgarian feta” was then fully rechristened to “Bulgarian white cheese” for marketing purposes within the EU – much like how the Danes adopted “Danish white cheese” for their successful and, some would say, superior version of “feta” that prompted Greece to seek protection for their feta in the first place. “Feta” is still the name for the Bulgarian product in countries such as the United States and Australia where EU PDO status is not recognised. In 2023, the Bulgarians in turn gained PDO status for their own Bulgarian white brine cheese, but since then there has been a push to adopt “sirene” as its international name as a way to streamline branding for this cheese across languages, marking its own identity and, above all, reflecting the way your average Bulgarian calls this cheese anyway.

Sirene is a staple for Bulgarians, and is used in such iconic Bulgarian dishes such as banitsa pastries and grated in snowstorm amounts atop of shopska salads.

Over the border in Macedonia, “sirenje” – or more accurately “belo sirenje” (lit. “white cheese”) – is still marketed outside of the EU as “Macedonian feta”, but same story as with the Bulgarian cheese, that’s no longer possible on PDO grounds in the EU. Likewise, Macedonian cheese producers have taken to using the term “sirenje” for export markets. However, there’s another white-ish Macedonian “sirenje” that has been making a name for itself lately and that is “bieno sirenje” i.e. “beaten cheese”, which describes the way this Macedonian cheese is produced and alludes to its texture. Seeing that “white brine cheese” has monopolised the word “sirenje” for itself, to distinguish from its more popular cheese variety cousin, “beaten cheese” is now more commonly referred to as just “bieno” (pronounced “bee-eno”) for both internal Macedonian and export marketing purposes.

So if the Macedonians and Bulgarians refer to their word for “cheese” as solely “white cheese”, then does that mean they don’t have yellow cheese?

They do! That’s where кашкавал (kashkaval) comes in.

Kashkaval is a distinct type of yellow cheese very popular not only throughout the Balkans but variants of this type of cheese are also found in southern Italy, the Middle East and into Poland and Russia. However, in practice with the Bulgarians and the Macedonians “kashkaval” is also the generic term for all types of yellow cheeses, whether it be Cheddar, Edam, Gouda, etc. The same goes for the Romanians and their “cașcaval”.

The origin of kashkaval is one wrapped in legend. Actually, every time I’ve written about it, I always get asked, particularly from Italians familiar with their own caciocavallo cheese, about where it came from. Essentially, everyone has their own origin story, of course attributing the cheese as belonging to their own country. Some say that the cheese does come from southern Italy and made its way to the Balkans during Ottoman times, from where it spread widely thanks to the empire’s extensive trade routes. Others say that it was the Arabs or the Albanians (the Arbëreshë) who introduced the cheese to the Italians. One common origin legend has it that was the transhumant, sheep-raring, nomadic Aromanians of the Balkans who invented the cheese. Now this has greater plausibility as the cheese is most often made from sheep’s milk and, on a linguistic basis, the word “kashkaval” can be attributed as a corruption of the Aromanian (a Romance language related to Romanian) for “carried on horses”. This article provides an insight into the complicated and contradicting theories and assumptions of the origin of kashkaval. Regardless of who invented it, what cannot be denied is that the Aromanians were most responsible for producing and transporting the cheese around the Balkans. Joining in on the trade were the scattered Jewish communities of the Balkans, who in Ottoman times were top customers for kashkaval, thanks to the nature of kosher diets rotating between meat and dairy, making milk products such as cheese a much more important part of their daily diet of Jewish people compared to other Balkan communities. It was this focus on the Jewish market which could explain the origin for the alternative name for kashkaval – “kashar” (the Ladino word for “kosher”) in Greece – “kasseri” – and Türkiye – “kaşar”. However, there isn’t sufficient evidence to back this claim, especially as Ottoman taxation documents from the early 20th century regularly listed kashkaval and kashar as two separate items, though this could have been out of nomenclature rather than actual different products.

A legacy of this Balkan Jewish connection is the popularity of sirene and kashkaval in Israel. White cheese is known as “Gvina Bulgarit” (“Bulgarian Cheese”) in Israel, where it had been introduced by Bulgaria’s saved Jewish community after making aliyah en masse in 1948. They not only popularised the cheese but they also went on to create something that I’m surprised that no-one in the Balkans has picked up on yet – spreadable Bulgarian cheese. Anyone who has had Balkan French toast would know how much this would be a god-send!

How did these two cheese varieties come to become the trademark generic names for their type of cheese? Now many would suggest that it’s because that these are the two types of cheeses that people in the Balkans have been eating since time immemorial, but the reality is quite different. Despite what may seem, it wasn’t until after World War II when cheese became a main part of the diets of Macedonians or Bulgarians. As what history professor Mary Neuburger outlined in her excellent book Ingredients of Change, The History and Culture of Food in Modern Bulgaria, what formed the modern national cuisines not only of Bulgaria but also of many other Balkan countries (and on that token, all nations) had less to do with “ancient traditional foods” or even nationalism and more to do with “the circulation of powerful food narratives—scientific, religious and ethical—along with peoples, goods, technologies and politics”. Major factors in determining what went into modern national cuisines have always been the availability of ingredients and modern distribution systems. The new borders that were mercilessly set after the appearance of the newly independent nation-states of the Balkans in the late 19th century did much to disrupt natural trade routes previously fully contained with the Ottoman Empire. These borders, often at odds with topographical concerns, led to changes in what foods were available. Most affected were the long nomadic paths of the cheese-making Aromanians, with the final blow being when post-WWII communist governments confiscated their huge sheep flocks, forced them into collectivisation and permanent settlement. This in turn saw the sale of many dairy products, the production of which had always been limited to highland areas suitable for raising dairy livestock, becoming very localised. This was particularly the case in Yugoslavia, especially after the early 1950s when Tito deemed the Stalinist-style collectivisation of agriculture to be a complete failure and ushered back a farming system primarily based on a patchwork of small-holders who did not have the means, land, facilities or livestock numbers to produce more labour-intensive products such as cheese. This resulted in Yugoslav Macedonia for kashkaval to be produced in much smaller numbers than before and only for sale in private markets near highland areas with large sheep numbers – Maleshevo, the Shar mountains and the rapidly depopulating Mariovo region. Kashkaval became an expensive luxury product. White brine cheese, which was much easier to produce at home, became for many Macedonians the only “sirenje”, hence its subsequent exclusive connotation.

Bulgaria’s post-WWII communist authorities, on the other hand, who stuck with mass collectivisation and greater centralised control with its fully planned economy and 5-year plans, saw protein, i.e. previously scarce meat and dairy products, as the future, bring the country’s diet to be more “European” in nature. With investment in modern manufacturing processes and planning focused on standardised products for greater efficiency, kashkaval cheese was singled out as the yellow cheese for Bulgaria’s growing (in all aspects) working class. Such was Bulgaria’s success at the industrial production of great quantities of high-quality kashkaval that for decades it was the most sought-after product for purchase from people crossing the border from Yugoslavia.

In the 1960s, people would meet up monthly in the no-man’s land between Bulgaria and Yugoslav Macedonia at the border between Stanke Lisichkovo and Delchevo. This would be the only opportunity for relatives on both sides of the border to see each other. These gatherings eventually turned into an impromptu market working solely on barter – it was illegal to export Yugoslav dinars or Bulgarian leva, and hardly anyone on either side at the time had access to hard currencies such as US dollars or West German marks. People on both sides of the border would exchange products for whatever was more readily available or in greater supply on the other side. For the Macedonians in Yugoslavia, that was easy as the poorer Bulgarians would snap up anything ranging from everyday goods that were in "deficit" to elusive western products unavailable in Bulgaria such as highly coveted blue jeans and (as what my father would take to exchange) records with western rock music. What did the Macedonians want from the Bulgarians in exchange? Cans of halva and, most of all, kashkaval.

After the fall of communism on both sides of the border and with free enterprise on the loose, Macedonians (and Serbs) still prized Bulgarian kashkaval so much that shops specialising selling the cheese lined the main roads leading from the border. The cross-border trade of kashkaval took on a greater scale in the 2000s with the phenomenon of the “torbari” i.e. “bag people” – petty smugglers who would cross the border from Macedonia to Bulgaria to buy cheap but good quality kashkaval at small quantities to bring back and sell at market stalls in Macedonian border towns. Weekends at crossing points on Bulgaria’s western borders would be packed with giant hordes of these torbari. It was only when Bitolska mlekara, one of the biggest dairy producers in Macedonia started making industrial amounts of its own line of kashkaval for mass distribution in the early 2000s, and then Bulgaria’s entry into the EU pushing kashkaval prices up that saw these circumstances change. Now that kashkaval is readily available inside Macedonia, and with the Bulgaria’s entry into the EU in 2007 pushing prices for kashkaval ever higher, the cheese shops that used to line the roads leading to the Macedonian border have now all closed. Meanwhile, for the past two decades, Bulgarians have complained that the quality of their kashkaval has dropped immensely. It doesn’t take long for a Bulgarian to cite the highly publicised cases when unscrupulous producers used milk substitutes and chemicals to make kashkaval. Nostalgists longing for Zhivkov often quote “kashkaval with no milk” as key evidence as to what’s gone wrong the most in Bulgaria since “evil capitalism came in and ruined the country”. So you can say that sometimes the "cheese” in Bulgaria is “not cheese”.

It’s only recently with the introduction and expansion of western-style, foreign-owned chain supermarkets that cheese varieties other than sirene/sirenje and kashkaval have appeared on food shelves in Bulgaria and Macedonia, but the dominance of these two local cheese varieties holds firm, and so to the terms for “cheese”. Your Edams, Goudas and Cheddars will just have to put up with being called “kashkaval” in these countries.

So to answer that curious translator, the generic term for “cheese” in Bulgarian and Macedonian is “сирене/сирење и кашкавал” (sirene/sirenje & kashkaval). Yes, a mouthful, but who doesn’t want a mouthful of these cheeses.

You want proof, you say? Well, here’s a photo of the cheese counter at a typical modern Bulgarian supermarket…

Needing someone to help you sort your kashkaval from sirenje? Translation from Bosnian to English, Croatian to English, Bulgarian to English, Macedonian to English, Montenegrin to English and Serbian to English can be tricky, but I can smooth it over for you like a good brie. Drop me a line at info@nicknasev.com and let's discuss. Cheese is extra! Have a gouda day!

.%20A%20day%20of%20campaigning%20%E2%99%80%20%E2%80%A6%20or%20a%20day%20to%20buy%20flowers%20%F0%9F%92%90.jpg)