25 May was a big day in Yugoslavia and its most 'socialist': Dan mladosti ('Youth Day' in Serbo-Croatian) and Tito's official birthday.

I say 'official' because Tito was actually born on 7 May 1892; however, 25 May was picked as it was the day when the operation known in ex-Yugoslavia as 'Desant na Drvar' (Raid on Drvar), i.e. Operation Rösselsprung was launched, when in 1944 Nazi forces attempted, and ultimately failed, to capture or kill Tito. The assault and its ultimate victory to Tito's partisans was celebrated as one of the most significant events in Yugoslavia's WWII history. It was also the subject of one of the most popular partisan films, Desant na Drvar, from 1963.

In the lead-up to the big day, there would be a relay throughout the country, known as Štafeta mladosti (Relay of Youth), starting in Tito’s birthplace, Kumrovec, Croatia. The relay would weave its way through every Yugoslav republic and autonomous province, ultimately arriving in Belgrade on 25 May to a stadium where a huge mass gymnastics display would be held, with Tito as guest of honour.

One of the main features of this relay was the baton, which would often be designed by Yugoslavia's most eminent artists and elaborately decorated in a melding of local folk and socialist motifs and, of course, regularly topped with a 'petokraka', the five-pointed star that was the main symbol of Yugoslavia, a flame or a regional but socialist symbol. The batons used throughout the years for this relay are on display in a room next at Tito’s grave in the Kuća cveća (House of Flowers) in Belgrade, so check them out if you're in town.

Young people who firmly displayed all the values and virtues promoted by Yugoslavia's Communist authorities would be selected to have the honour to run with the baton in the Relay of Youth. We're talking about good, hardworking youth from proper working-class origins who've been unswerving in their loyalty to Yugoslavia's communist leadership and, above all, Tito. But things didn't always to go to plan in this respect...

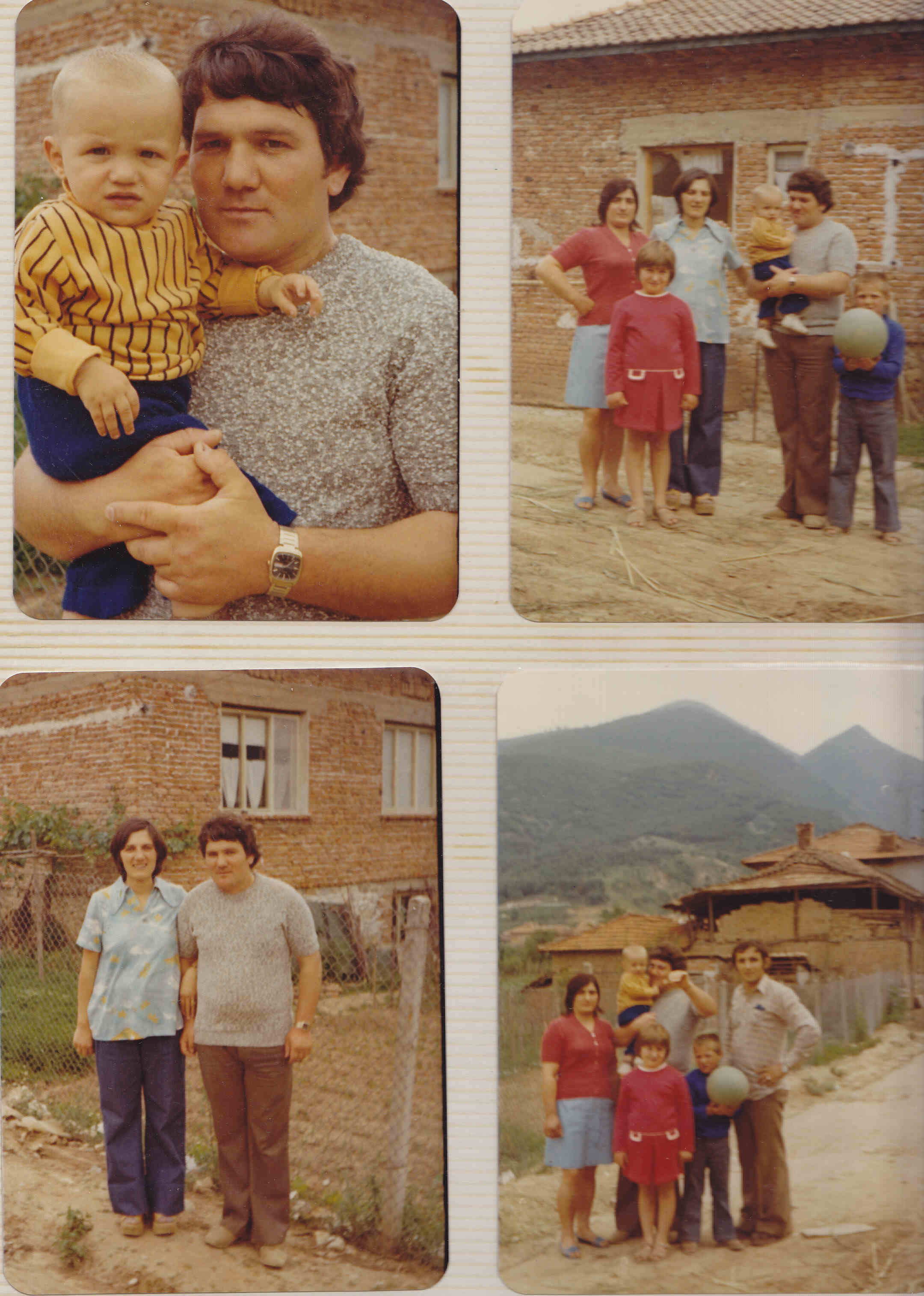

My father once ran with the baton! Yes, he had the honour to do so... but he wasn't supposed to. It was a major accident! Here's the story.

It was early May in the mid 1960s. My father, a teenager at the time, was living in a village right next to the Macedonian city of Kochani. He was innocently walking into town when all of sudden huge crowds descended and lined the side of the road. Now, my father, to put it lightly, in the eyes of his teachers was not the most politically reliable of teenagers. Yes, he excelled scholastically and was a gifted football player, but he would often be marked down for not toeing the line expected from an upstanding citizen of socialist Yugoslavia whose father had impeccable WWII partisan credentials. Now. I'd have liked to say that my father's defiance was out of a form of political protest stemming from a firm personal conviction for justice and freedom against the oppression of Yugoslavia's one-party system. Alas no, this was more out that purest of Balkan behaviours – inat. Open Democracy best defined inat as 'an attitude of proud defiance, stubbornness and self-preservation – often to the detriment of oneself and/or everyone else'. It's being opposite for the sake of being opposite; it's not a virtue but a curse. Inat is not just an attitude but an oft unfortunate Balkan way of life.

Unperturbed by the crowds, my father continued his way down the road... until there was a tap on his back. He turned around startled. Suddenly, my father was handed a baton... the Relay of Youth baton! Not knowing what to do, instinct kicked in and so he decided to play along with the whole spectacle and started running with the baton. He certainly enjoyed not just the exhilaration from the cheering crowds but also from knowing that he was the last person the Yugoslav authorities would have picked to run in the Relay of Youth. The people in the crowd from his village were in shock as they knew what my father was like. Apparently it took some time before the local relay organisers realised that the baton had been handed to the 'wrong' person, and quickly rectified the situation embarrassingly play-acting in front of the crowds as if everything was going as scripted.

This story is regularly brought up at family gatherings, and every time any of my family members go the House of Flowers, we always check out the batons to see the one that had my father's grubby mitts on it.

The relay culminated in the evening of Youth Day in Yugoslavia's capital city Belgrade with that pinnacle of 20th century communist events – a mass gymnastics display, complete with a cast of thousands of small children to young adults from all around Yugoslavia. The origin of these displays was from the pan-Slavic Sokol movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which promoted mass involvement in exercise. Mass gatherings would finish with a mass event called a ‘slet' where hundreds to thousands of participants would perform a choreography of the same basic exercises. Communist propagandists appropriated these mass displays for their own purposes, with Yugoslavia being no exception. One aspect, though, of the slets in socialist Yugoslavia, especially when compared to the pinpoint precision and bravado characteristic of mass gymnastics displays in the likes of DPR Korea, was the more relaxed nature to them – the images formed by the thousands of young people weren't always perfect and not all of the participants would be in complete sync with the others, but that didn't matter. These imperfections were a fitting reflection of the relatively freer nature of Yugoslav socialism.

The slets would regularly feature themes typical of communist iconography, emphasising the 'brotherhood and unity' of Yugoslavia, the main role of the military and that the lynchpin to it all was Tito. Yugoslav rock music, here devotional to Tito, Yugoslavia and the Communist Party, provided the soundtrack, musically linking the event to its ostensible celebration of youth. This also outwardly and very publicly espoused official Yugoslav socialist cultural policy of co-opting forms of artistic expression that other socialist countries, particularly in neighbouring countries, frowned upon, but I have to admit that there was a slight bit of inat working here too.

The slet would culminate with the entry of the relay runners who would eventually hand the baton into the crowd who, with much symbolism, then pass it up to the rostrum where Tito (or later, head of the Praesidium) was seated. The final person to handle the baton and read out the message contained in it on behalf of the youth of Yugoslavia to Tito or the 1980s leadership would be selected from among the best students or young workers that year in all of Yugoslavia. Like the relay runners, this young person would also be of proper working-class origin and a devoted member of the Mladina, the Socialist Youth wing of the Yugoslav League of Communists. All six republics and two autonomous provinces would be represented in this role by yearly rotation (e.g. it was an ethnic Albanian from Kosovo in 1979 and 1987), and in true Yugoslav style displaying (at least a superficial) respect for minority rights, these messages to Tito would start in the person's native language where this was not Serbo-Croatian.

45 years ago today, as a small child I saw my first ever slet broadcast live on TV in Yugoslavia. I remember it being the most spectacular thing I had ever seen to then. Normally a joyous event, the atmosphere at the 1980 slet was subdued as the usual guest of honour, Tito, had died only 3 weeks earlier, making this the first Dan mladosti slet without him.

The last relay and slet happened in 1988 when the writing was already on the wall as to Yugoslavia's future. The scandals surrounding the 1987 Youth Day brought the event to a sudden end. The design division of Slovenia's Neue Slowenische Kunst punk art collective (Slovenian band Laibach being the collective's most famous members) won the competition for the 1987 poster, raising many eyebrows. However, it was later found that their posted was based on a Nazi propaganda poster, the politically commentary associated with this being true to their ethos. The imagery in the poster, starkly drawing the direct correlation between the torch relays of Nazism with that of Yugoslavia's Relay of Youth, quickly prompted a reconception of the actual baton. The 1988 relay then featured a last-ditch baton replacement in the form of perspex box containing eight drops of blood, one each from Yugoslavia's constituent entities. The use of blood though would end up being ghoulish considering the unprecedented bloodshed that would engulf the country just three years later.

Still, ask people from Yugoslavia over 45 years old about the relay and slet and often you'll get fond youthful memories, especially from those who had the fortune to participate in these events. Memories of a peaceful past forever lost. Today remains, as it was intended, a symbol of an idealised Yugoslavia – unified in diversity, at peace though ready for war, (seemingly) disciplined and functional, but always human and colourful.

.%20A%20day%20of%20campaigning%20%E2%99%80%20%E2%80%A6%20or%20a%20day%20to%20buy%20flowers%20%F0%9F%92%90.jpg)