Borders points are weird places, especially in the Balkans. Hour-long queues, border officials ranging from the kindest people in the world to outright criminal, and locations that at times are nondescript, at times with the most spectacular scenery you’ll ever see. It’s where those invisible lines called borders provide this force field locking out most of the other side’s culture, language, references, experiences, outlooks, worldviews and people.

I have many Balkan border crossing stories to share, so time to unleash them. Here’s the first…

Have you ever travelled through 4 countries in less than 24 hours? It’s something very achievable in the Balkans. The first time I did so was on 15 July 2003.

I left Belgrade, Serbia by bus to go via Croatia to Ljubljana, Slovenia, and hopped on a train that took me to Mestre, Italy. Then caught a train full of American backpackers to Verona, and then driven to Trento. 3 new countries and lots of miles covered.

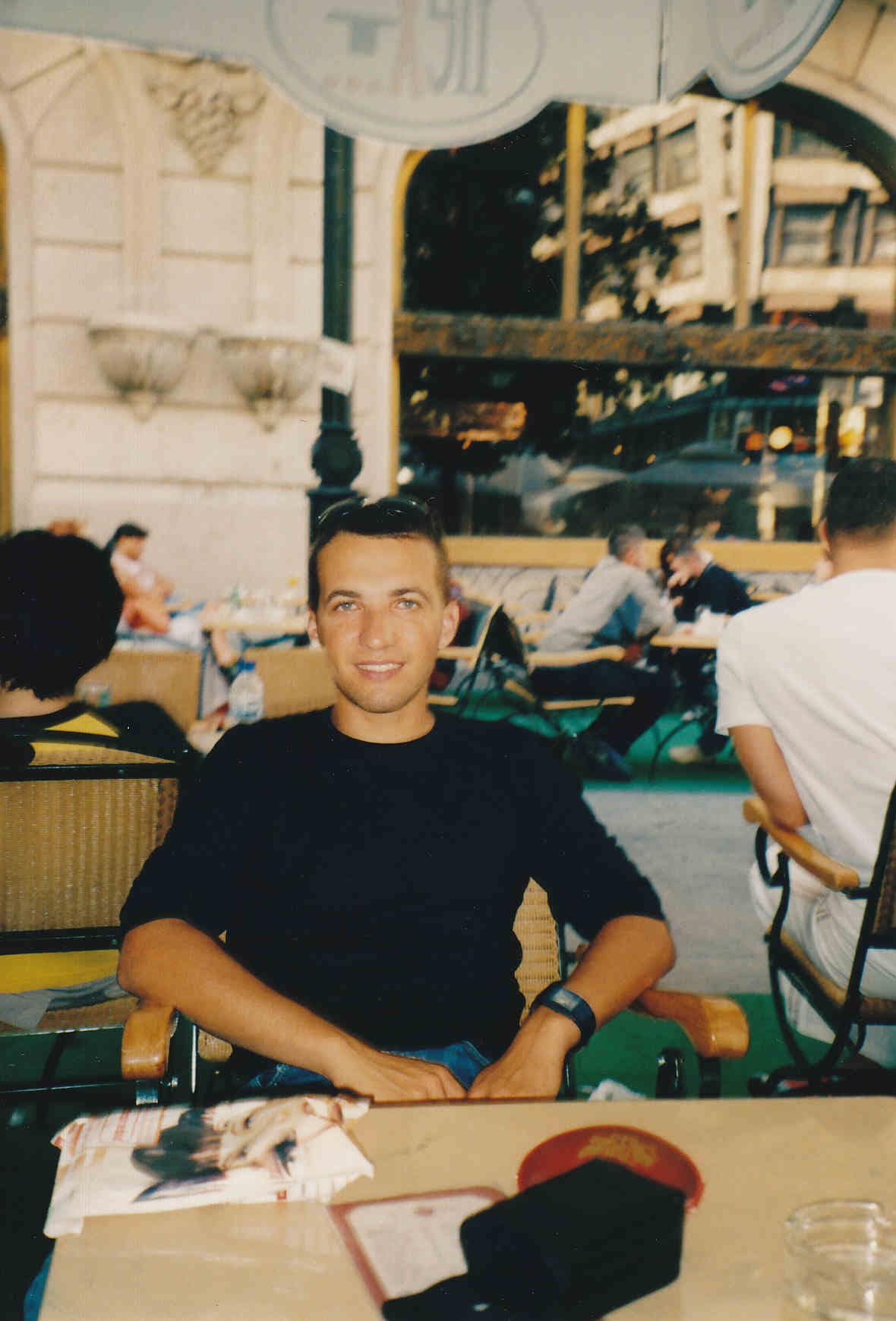

I had spent two weeks in Belgrade with my father’s cousin, who lived a comfy life in one of Belgrade’s nicer suburbs. Let’s just say that having had a father who had been a high-ranking official in the Yugoslav People’s Navy, and all the privileges that came with it, certainly paid off. I also visited his mother, who as a child I used to call ‘Vujna baba Mica’ (Auntie Granny Mica) as she loathed to be called a granny, but 5-year-old me couldn’t understand how come.

Next stop after my sojourn in a sweltering Belgrade was visiting Vasko, a cousin of mine in Trento, Italy. Vasko was a truck driver… and always the life of the party, easily making friends with anyone. He had been living in Italy since the late 1980s, which he then describing being “poorer than Yugoslavia” but that sure had changed. We first met in 1997 when we both were visiting our families in Macedonia. Vasko practically kidnapped me and took me to see all the kafanas of his home village, eager to point out that everyone in his village was also some distant relative of mine. In between the number of beers I had lost count drinking, Vasko out of the blue says “That’s it, we’re off…”

- “Off where?” I asked puzzled.

- “France! I'm taking you to France right now! You’re joining me with my truck driving.”

Partly thrilled by the chance on offer and the serendipity of it all (take it from me, the best travel is unplanned), reason quickly kicked into my inebriated mind. I mean, as much as I would’ve loved to jump at this opportunity, I had a return flight to Australia in a week’s time and work waiting for me there. It just wasn’t feasible. But Vasko drives a hard bargain and doesn’t take no for an answer. Then I worked out a bureaucratic hitch that could get me out of this conundrum without bruised souls.

- “Sorry Vasko, Australian passport holders need visas to enter France and it’s going to take some time to get it.”

I was saying the truth here. Until 1999, in an act of reciprocity, France required visas from Australian citizens. Not New Zealanders though, who at the time had the better passport thanks to their less restrictive entry requirements for visitors.

Vasko certainly understood the predicament. Anyone in the Balkans can tell you their horror stories of applying for visas – the huge amount of paperwork, the endless hours (even days) waiting outside of embassies, the relatively huge fees, the humiliating interviews, and all with no guarantee that they’ll be granted the much prized visa.

So Vasko made me promise then that the next time I’m in Europe and free, he’ll honour his invitation to see Europe from a truck driver’s perspective.

And so he did! In 2003, while I was in Macedonia after a family circumstance which saw me looking after my grandfather for an extended period of time, Vasko calls me and the first thing he asks is: “Are you ready to come with me on that trip?” Actually, I was hugely delighted that he remembered. So that summer I took him up on his offer and, yes, he took me to France.

Before getting to Trento, I had been around the Balkans, spending quality time with relatives and building up my knowledge of my Slavic languages. It was the perfect place for it as no-one spoke English. What I wanted to do is go and visit Serbia for the first time ever. The difficulty of Australians obtaining visas for Serbia (requiring official letters of invitation) stopped me from going, but Macedonian passport holders had no such requirements, so that was part of the reason why I obtained my Macedonian passport that year (oh, there’s a great story there about Balkan bureaucracy, but that’s for another time). Of course, only days after I receive my Macedonian passport, the Serbian Foreign Ministry announces that Australians (and many other western nationalities) no longer require visas for Serbia. Just my luck!

After making it to Belgrade and spending a wonderful week getting to see the city from a local perspective, Vasko had organised so that a bus going direct from Skopje to Italy would make an impromptu stop in Belgrade to pick me up. So off I went to a spot right after the Gazela Bridge next to the Sava Centar. Waiting, waiting, waiting. My father’s cousin and I start thinking we’ve missed the bus. Oh no, there it comes… and thunders right past me. So that extended my stay in Belgrade for another week, which I didn’t mind. OK, time for Plan B and getting to Italy on my own steam.

Easily done! There were plenty of buses going from Belgrade to Italy, so I bought a ticket. But just as I was walking away from the tin shed passing off as a ticket office, I realised I forgot to ask one major question – does the bus go through Hungary? Alas, it did – all buses from Serbia to Italy did, a legacy from the 1990s Balkan war years when travel through Croatia was not possible. But where Serbian citizens could travel visa-free through Hungary at the time (primarily to facilitate ties with the many ethnic Hungarians in Vojvodina), that wasn’t the case for Australians and Macedonians. Thwarted again!

Plan C then kicked in, which meant getting to Slovenia and then making my way to Italy from there. Fair enough. And luckily enough, travelling from Belgrade to Ljubljana was a bit more straightforward. For starters, despite the international borders that had been in place for over a decade, all destinations in ex-Yugoslavia were still being treated as domestic. And in a tentative post-war goodwill gesture, Croatia had then just lifted visas for Serbian citizens, so buses to Ljubljana were going direct via Croatia (I checked this time before booking). But with hostilities still fresh, many Serbs were still reluctant to enter into “enemy territory”. As it turned out, the bus I caught was not that full – mainly young Serbs living and/or studying in Slovenia.

Off we went from Belgrade’s iconic bus station that was next to its rather demure railway station. And how insightful (or most likely an unexpected coincidence) that the Serbian acronym for the Belgrade bus station – “BAS”, is pronounced the same as “bus” in English. So whenever a lost English-speaking traveller needed to ask any local for a “bus”, the Belgrader would be able to point the way to Belgrade’s bus station. There was an outpouring of nostalgia mixed with some anger when Belgrade’s bus station in its city centre closed in September 2024 (the clip of the final bus leaving went viral) and replaced by a new station across the Sava river in Novi Beograd.

It takes just under 2 hours across the flat terrain of Syrmia, the southern part of the Pannonian plain, to get to the Serb/Croat border. No hold-ups or ethnic prejudices on the part of the Croat officials for our Serbian-registered bus. Quite the opposite, in that the Croat officials seemed to be like old friends with the Serb bus driver and assistant. I decided I’d enter Croatia using my Australian passport. Most border officials find Aussies trustworthy – we’re not the types who end up overstaying, and we have cuddly wildlife to boot, so procedures at borders end up being quick for us, save for the occasion banter about snakes and sharks. And if there’s one Balkan trait I certainly have, then it’s a fear of dealing with obstinate and discriminatory border officials.

A few hours later, after making it through Croatia along the motorway that used to be named ‘brotherhood and unity’, a complete irony considering what had happened in the region in the previous 15 years, we reached the Croatian/Slovenian border. Uneventful so far, but wait…

The Croatian border guard came onto the bus and individually took everyone’s passport after giving everyone of us a rather sinister look. This one took his job a notch too seriously. The border guard got to me. I hand over my Australian passport, gave the obligatory scratch at where the photo is (at the time, Australian passports were one of the few that had the photo integrated into the page), lingered a bit longer checking it, and then he continued his way towards the back of the bus. All fine… or so I prematurely thought.

The guard had collected all the passports, but as he passed me, he indicated with a hand gesture that I had to come with him, which I found surprising, and so too all the other passengers. I had to take my giant backpack with me from the baggage hold too. “That’s it” I thought. “I betya I going to be held here and the bus goes off without me.” Anyway, I thought I’d play cool because, hey, what have I done wrong?

The official starts interrogating me in Croatian. I thought that was a bit presumptuous, given that I had an Australian passport – there was nothing apart from the “-ev” ending of my surname to suggest that I was even a Slavic speaker of any sort. Perhaps it was my look and clothing, so I must have assimilated well and convincingly after so many months in Macedonia. I did reply to his first two questions in Croatian, telling him of my time looking after my grandfather and I even showed him my Macedonian passport. He asked me why didn’t I enter with my Macedonian passport then? That’s when I gave up being on his terms with speaking in Croatian and switched to answering in Macedonian, which Croats usually only get the jist of understanding. He continued with the interrogation, asking me where I was heading, what job do I do, etc. I asked him why am I being asked these questions but he didn’t give any answer, well, at least verbally – the smile he gave when I asked said more. You see, when someone in the Balkans smiles like that in such a situation, it’s not a good sign. In any case, I continued to answer his stupid questions (as most questions in interrogations are – it’s a tactic to get you so annoyed that you erupt) but with as little words as necessary, all still in Macedonian. Each response from me was filled with contempt and could have come with subtitles saying “you’re an idiot, mate!” In the corner of my eyes, I could see everyone from the bus was watching through the bus window at what was happening in the booth. The border guard and I certainly provided some enthralling viewing for them (real-life Border Control hehe!).

After 10 minutes of this joke of a situation, it was clear that the border guard was not only wasting my time but his, but still he had to go through the motions. He ordered that I open up my carefully packed backpack, which I have to admit was mainly filled with newly purchased cassettes and CDs of Balkan Turbofolk (très moi!). A cassette of new Turkish chalga songs from Bulgaria (curiously with the Turkish written in Bulgarian Cyrillic) caught the border guard’s eye the most. He held it up and said to me “ah, this one’s from Macedonia” showing his ignorance of the Cyrillic alphabet. I curtly said “yeah” and just looked at him with that look saying “so what?”. It was clear that there was no reason at all for what was happening and that the best thing to do would be that he stamp my passport and let me, and for that matter, the rest of the passengers of our bus, to go. But no… he had to go through all my stamps and ask random questions about them. He saw the my US stamp and asked if I had been to the USA? Well, durr! While sifting through my passport in that way that people with too much power and too little brains only can, he kept saying to me mockingly “svjetski putnik” – Croatian for “world traveller” as if being one is something of a crime or possibly alluding that I’m some sort of spy (I get that one often, mainly from people from central and eastern Europe). However, it was more out of inat, that all-pervasive Balkan small-mindedness that can’t be succinctly translated into English in the one word. Here the official thought that I was better than him (OK, I did think that) and that he was now turning the tables as such to teach me a lesson of sorts. Wow, what a victory (that’s sarcasm)! Yeah, I think we can see who was the silly one here… and it wasn’t me. Reluctantly, he finally stamped my passport, I quickly packed my backpack, got out of the border post booth and the bus driver was there ready to close the baggage hold after I had chucked my backpack in. Relief!

I had the walk of shame down the aisle of the bus and took my seat. That’s when everyone around me had to ask me what happened. Of course, the whole bus was interested in getting the full gory details of what occurred (Balkan people always are), so my answers were then also being relayed by others to the people towards the front. There wasn’t really much to say, but it did prompt a lot of talk and major scorn of power-hungry border officials from my fellow passengers. It also broke the ice and I got to find out a lot about the people travelling to Ljubljana. Most of them were Serbs studying at universities in Slovenia. One guy, who was studying architecture in Ljubljana and living with his auntie and uncle, told me that he had plenty of Macedonian friends on account that the Serbs and Macedonians seemed to have far more in common than with the Slovenians. He said the Serbs and Macedonians watched the same cartoons as children, but the Slovenes had rather different programming, and so their cultural references didn’t line up as much.

This journey I was doing on that day was part of a longer trip that took me from the Black Sea in Bulgaria, across Europe and later to northern coast of France. I had been told that in travelling across that the biggest change occurs between Croatia and Slovenia, a distinction that even existed when both countries were once together in Yugoslavia. I had noticed that when I crossed from Bulgaria to Serbia for the first time that Serbia was slightly cleaner and more organised, and had inherited and maintained its infrastructure from socialist Yugoslavia at a better standard than in Macedonia. I didn’t notice much difference between Croatia and Serbia, but immediately entering Slovenia, it was like chalk and cheese. It was clear I was entering a different, more efficient world. I noticed the little things such as the nicely tended flower boxes hanging from windows, giving houses a look straight out of a fairytale. After being in the scruffiness of the Balkans for many months, Slovenia seemed antiseptically clean.

Over an hour later, and having driven our way through the spectacular mountainous Slovenian countryside, we made it to Ljubljana, where my next task was to find out how to get to Mestre, Italy. There weren’t any buses, but was instructed to go and ask at the railway station next door to Ljubljana’s central bus station. And what luck… there was a train direct to Mestre via Trieste in an hour! Some things were meant to be.

Welcome to country number four for the day and my first time in Italy!

The sunset over the Gulf of Trieste as seen from the train was stunning. I had been speaking in Macedonian, Bulgarian and Serbian exclusively for months up to then, so talking to some of the other passengers exposed how rusty I had become with English. But being fluent in English is a privilege that native speakers rarely comprehend. That was apparent at the railway station in Mestre where amidst the chaos of the ticket office, a woman approached me asking if I can speak English. I said I could, and so she asked if I could help her buy a ticket for a train to Udine. She was from England and was on her way to visit a friend, but clearly it was her first time in Italy, and being in that environment, she could be forgiven for being a tad overwhelmed. I took her to the automated machines where a minute before I had bought a ticket for Verona. Automated machines with language options were somewhat new at the time, but from the beginning, these machines have always had an English option. That’s where English-speakers are privileged. Now imagine a speaker of another language and not knowing English? International travel is then extremely daunting. It astounds me that relatives of mine who know absolutely no English have managed to travel to Australia from the Balkans and back. I don’t know if I could have done that had I been in their situation. I showed the English woman the English option and proceeded to book the ticket. She was so thankful, and I hope she had a great time in Udine.

After a late train trip to Verona, my cousin met up with me there and then he drove the final 100 kms past castle after castle to Trento.

1000 kms covered in one day: one bus, two trains, two cars, one interrogation, four countries. Travel!

So what was the most important tip I gained from this trip?

- I always use my Macedonian passport when I travel within ex-Yugoslavia.

And what a major plus it’s been! The border guards are glad that they can speak to me in their language, and there’s this sort of understanding that I’m “one of us” i.e. “Yugoslav”, where I’m on the same wavelength and footing as them. It’s this unwritten camaraderie that despite what happened in the late 1980s and 1990s, everyone in ex-Yugoslavia is still fine (well, to a degree). This certainly gets me across intra-Yugoslav borders much quicker. For entry to Serbia, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina, even a Macedonian ID is sufficient, so it’s usually a show of the passport and up goes the boom bar. The Australian passport, especially with my identifiably Slavic surname, elicits the extremely negative stereotypes in the region often associated with the diaspora in Australia of boorish, uncouth, money-splashing, brash uber-nationalists. So when Macedonians disparagingly ask me what use is a Macedonian passport for me when I have a prestigious Australian passport, then I tell them how much more respect I get for having the former when in ex-Yugoslavia.

Border points and the interesting scenarios that happen at them feature heavily in my travel stories, so stay tuned as I gradually bring them to light. Expect marching through unseasonal snow, machine guns, broken vodka bottles, perfume smuggling, t-shirt smuggling, drug smuggling, cigarette smuggling, six-hour waits, bribes, the works!

Happy travels!

.%20A%20day%20of%20campaigning%20%E2%99%80%20%E2%80%A6%20or%20a%20day%20to%20buy%20flowers%20%F0%9F%92%90.jpg)