‘Fellow traveller Zhivkov’

This is something that appeared in a translation from Bulgarian into English I edited some years ago.

What's this? Well, obviously the translator had no idea who this Zhivkov was, and I have no idea how come the once supreme ruler of communist Bulgaria was then relegated to a low-ranked ‘fellow traveller’.

The original text was ‘другар Живков’ (‘drugar Zhivkov’), which translates as ‘Comrade Zhivkov’, the general title used for Todor Zhivkov, the Communist dictator who ruled Bulgaria in one way or another from 1954 to 1989 and the most important figure in the country's history this past century. The legacy of the time of Бай Тоше (‘Bay Toshe’), another common nickname for Zhivkov, ‘bay’ meaning ‘esquire’ in Turkish and used as a slightly ironic term of honour, is still very much evident in all facets of Bulgarian society, ranging from the apartment blocks that most Bulgarians live in to the way (particularly older) Bulgarians often make casual references of the terms used from that time. It is an aspect so important and embedded into modern Bulgarian culture that not just translators but anyone learning Bulgarian or even living in Bulgaria needs to acquire at least a basic understanding of it.

Here are some examples:

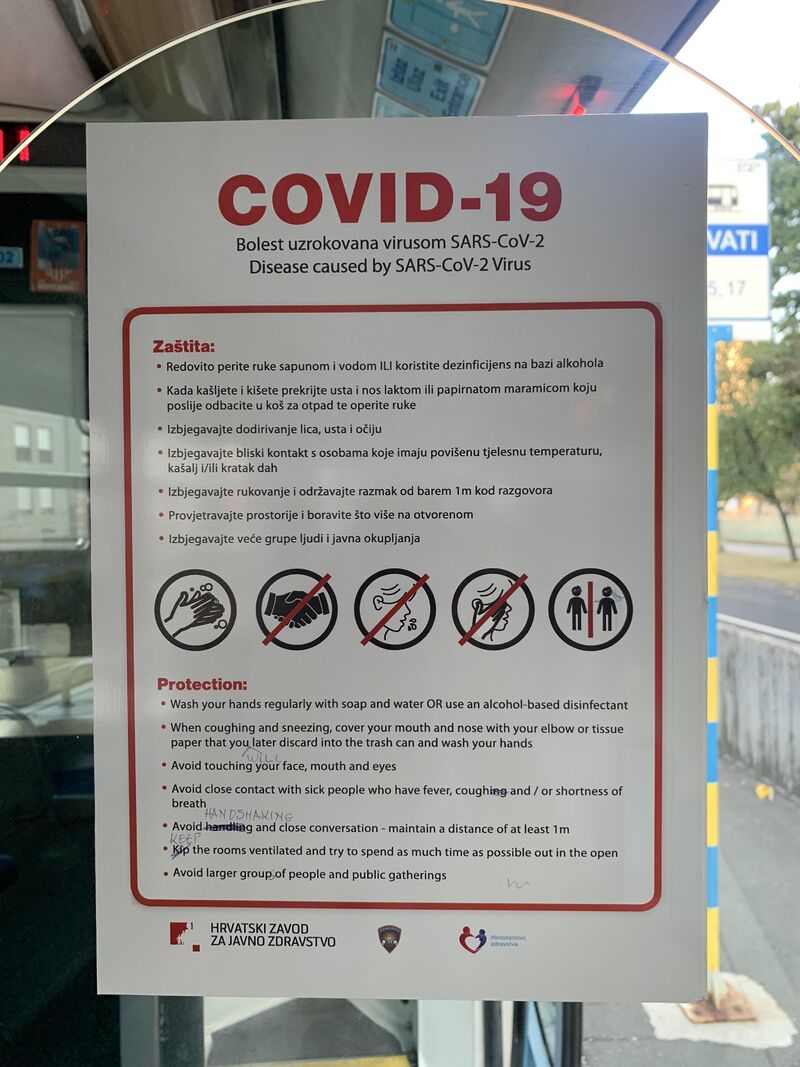

When Bulgarians talk of a дефицит (‘deficit’), then they’re referring to the term used for the perennial shortages of desirable goods so unfortunately characteristic of communist Bulgaria. The dreaded режим (‘rezhim’) is not about the political ‘regime’ but to restrictions on water or electricity – such as hot water would be on ‘rezhim’ at only between 6 pm and 10 pm. When older Bulgarians refer to Союза (‘Soyuza’ – lit. ‘the Union’), they mean the Soviet Union, though some would ironically apply to the European Union these days, much like how Bulgaria’s answer to David Letterman and the biggest celebrity/musician-turn-politician in the country, Slavi Trifonov, would satirically refer to other EU countries as ‘братски’ (‘brotherly’) as was the practice during communism when referring to the then ‘brotherly’ Eastern Bloc countries. Friday-night viewing on Bulgarian TV pre-1989 was fully in Russian with no subtitles, with the obligatory WWII Soviet film, so asking if a film is ‘Russian’ is a way of asking if it’s boring, or that when two women couple-dance together that’s ‘dancing Russian style’, a reference to the huge demographic impact of the millions of Soviet citizens lost in WWII resulting in women heavily outnumbering men in the USSR.

Going back to ‘drugar’, this was the general term that Bulgarians used for ‘comrade’ with each other during communist times. However, it essentially means ‘close friend’, so context and tone determines whether a Bulgarian actually here means an actual best buddy or jokingly in its Communist sense.

Then there are communist-era terms, many of which even get younger Bulgarians confused. These include петилетка (‘petiletka’) aka ‘the five-year plan’, ТКЗС (‘TKZS’) - the initials for what were collective farms, and жителство (‘zhitelstvo’) - the residence permission, much sought after by people in the provinces, required to live in the big cities, especially the capital Sofia. One communist-era term inherited from the USSR and, to a minor degree, persists meaning ‘communal voluntary work’ is съботник (‘sabotnik’), a reference to ‘Leninski sabotnik’, the communal spring-clean that used to take place around Lenin’s birthday on 22nd April. This was when whole neighbourhoods would ‘voluntarily’ clean up the neighbourhood of rubbish, weeds and breakages caused mainly from the winter that had just finished. And watch out whether преустройство (‘preustroystvo’) refers to your run-of-the-mill ‘reconstruction’ or to the late 1980s Bulgarian equivalent of what is better known in the west by its Soviet name, perestroika.

Then you get Bulgarians regularly going on about having a луд купон (‘lud kupon’), literally a ‘crazy coupon’.

Would you believe that this is the Bulgarian way of saying ‘wild party’.

No one really knows how or when a ‘coupon’ equated a party, but if you want to get Bulgarians talking, start this topic up on any social media platform and watch it all implode.

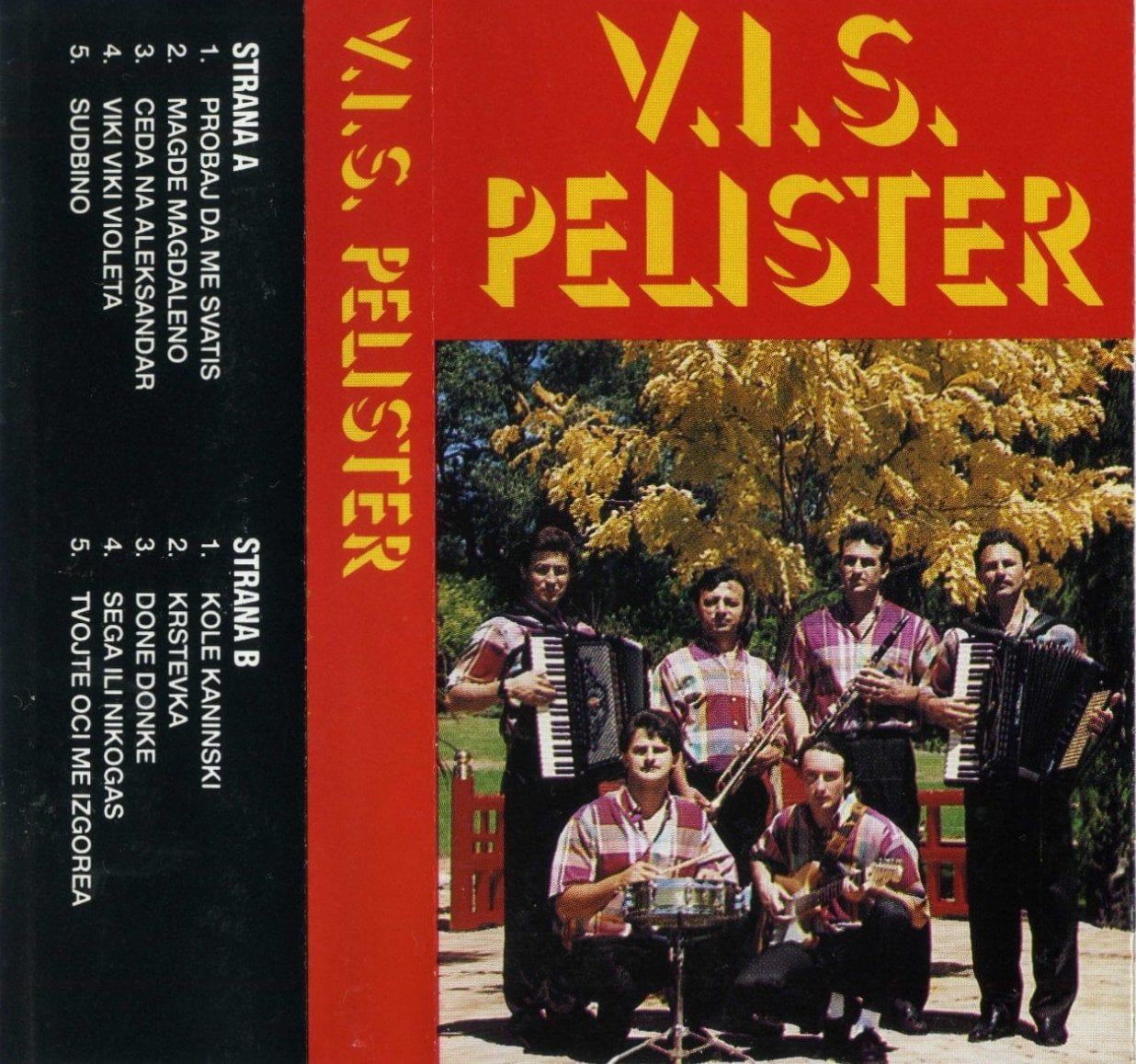

Some Bulgarians claim that the ‘coupon’ refers to those given as a reward for exceptional workers during communist times granting them entry to fancy, i.e. hard currency-only, venues such as high-end restaurants and nightclubs aimed at foreign tourists. Others claim the ‘kupon’ is from the early 1990s when for a brief period the local currency was in the form of ‘coupons’, so having any meant using them up quickly and having a fun time. On a linguistic basis, it could come from the Bulgarian word куп (‘kup’), meaning ‘a gathering of people’, though why then ‘-on’ was added, not a typical Bulgarian ending, makes the relation more of a coincidence. Of course there’s also a verb to go with it: купонясвам (‘kuponyasvam’) meaning ‘to party’, so this weekend there’ll be people who купонясват жестоко (party hard), perhaps to Bulgarian chalga star Sonia Nemska, who here is bringing the house down with her ‘Lud kupon’ for a million (people)…

One term from Bulgaria’s communist period that still evokes intense levels of rose-tinted nostalgia is бригада (‘brigada’) i.e. ‘brigade’. Here’s the story. You in the west had it pretty easy when it came to summer break from school and university as that often meant months of fun and no work. That wasn’t the case for Bulgarian pupils and students. No, they went off to do ‘voluntary’ unpaid work (there it is again) as brigades. Bulgaria’s English-language Vagabond magazine goes into wonderful detail about what the brigades involved, warts and all, but as is often the case with nostalgia for the good ol’ days of youth, many Bulgarians gloss over the less pleasant aspects of the experience (such as back-breaking work in the baking sun) and instead make it out to have been like some 1960s summer holiday film: “they paint idyllic pictures of hard, honest toil in the daytime followed by romantic nights spent singing round campfires”.

Forward to the 21st century and around Bulgaria you’ll still hear people talk about working in a ‘brigada’, only now these brigades are not summer camps in the Bulgarian countryside but refers to seasonal agricultural work picking fruit or vegetables in countries such as the UK, Germany and Italy. So yes, recruiters have unscrupulously adopted the term ‘brigada’, taking advantage of the idealised nostalgia associated with this word, to portray what is often exploitative and poorly paid work with dire work conditions as some sort of summer frolic. I’ve even had full-blown arguments with relatives about this. When I told them about the stark realities of agricultural work in the UK, they assuredly countered whatever I had to say by claiming ‘but they’re on a brigada’.

The person who had translated the text about our fellow traveller Zhivkov was an English retiree who, unlike many of their compatriots, had acquired a basic knowledge of Bulgarian from living in a retirement complex on the Black Sea Coast. That this retiree made the effort to learn Bulgarian is something to be commended and encouraged, though being confident enough to be able to translate text from colloquial Bulgarian was maybe a little too beyond. Many people think that learning a language, and translation for that matter, is simply swapping one word in one language into the other, but ask any linguist and they'll tell you how every word and phrase comes with baggage, a cultural and social context, making communication more than superficial. There’s always different connotations to every word depending on language and society. This then means mastering a language and adapting to living in another country also requires understanding of the culture and the country’s past.

Now can AI do what translators do? Absolutely not! When seeking the services of translators, be sure to find out how much they have a grasp of the culture and context of the source and target languages, for if they have very little idea of the full picture, then the good money you're paying for translation will then be going to a distant fellow traveller rather than a true comrade.

Talking of comrades, let’s finish off with some hard-hitting chalga with a political twist. The late Panayot Naydenov, better known as Panko, released this tongue-in-cheek number in 2003 ostensibly celebrating Zhivkov but actually taking a subtle jab at the nostalgia that many Bulgarians have for the period of ‘real socialism’ (as the propaganda at the time described it) that Тато (‘Tato’ – i.e. ‘daddy’, another colloquial term for the big guy) presided. This gets the hoofers onto the dance floor whenever it plays at a village disco, as I’ve witnessed many a time. Even young people who weren’t even a twinkle in their parents’ eyes when Zhivkov was deposed in 1989 get right into it. So dust off your Hero of Socialist Labour medals and bop to Evala Zhivkov (Hooray to Zhivkov!).

.%20A%20day%20of%20campaigning%20%E2%99%80%20%E2%80%A6%20or%20a%20day%20to%20buy%20flowers%20%F0%9F%92%90.jpg)