In late July 2025, singing superstar Dua Lipa, born in the UK to Kosovar Albanian parents (her father and manager Dukagjin was a rock musician, if you didn’t know) was granted Kosovo citizenship, raising her passport count to three — the United Kingdom (her birthplace), Albania in 2022 and now her ancestral Kosovo. Honestly, we’re all surprised that she didn’t have citizenship beforehand as she had lived in Kosovo as a child.

When granted Albanian citizenship in 2022, Dua Lipa spoke in Albanian to express her gratitude on how proud she is of her ethnic origin. After being handed her newly minted Albanian passport, Dua Lipa said that she now has "dy pasosha" (two passports).

“Pasosha”? Is that Albanian?

Well, yes, just that Dua Lipa was speaking in the modern colloquial form of Albanian as spoken in Kosovo.

Like many of the languages in the region, Albanian has a large number of differing dialects, still very much spoken, with the two largest groups being Gheg Albanian in northern Albania, Kosovo, Montenegro and most of the Albanian-populated areas of N. Macedonia; and Tosk Albanian in southern Albania, Greece and southwestern N. Macedonia. Within these two groups there are literally dozens of sub-dialects, traditionally the product of the mountainous nature of the Balkans resulting in isolated groups forming their own speech patterns and words. However, there’s also been another factor in the formation of newer dialects — borders.

It was only in 1972 when a final agreement was made on the standardisation of Albanian. Until then, there had been an ongoing battle between Gheg and Tosk groups on what dialect should form the basis for the standardised, prestige form of their shared language, and how many elements from each major dialect group should go into it. With Enver Hoxha and most of the senior communist leadership in Albania hailing from the south of the country, the current standardised form then was heavily based on their Tosk dialect. However, the borders drawn and then settled in the years 1912–1918 had seen many, predominantly Gheg, Albanian-speakers ending up in what was to be called Yugoslavia and with Serbo-Croatian as the new country’s de facto national language of administration and commerce. This, plus the Cold War years where in its self-imposed ideological isolation Albania sealed the border tight with ally-turn-enemy Yugoslavia, two rather separate environments emerged where the Albanian language would evolve.

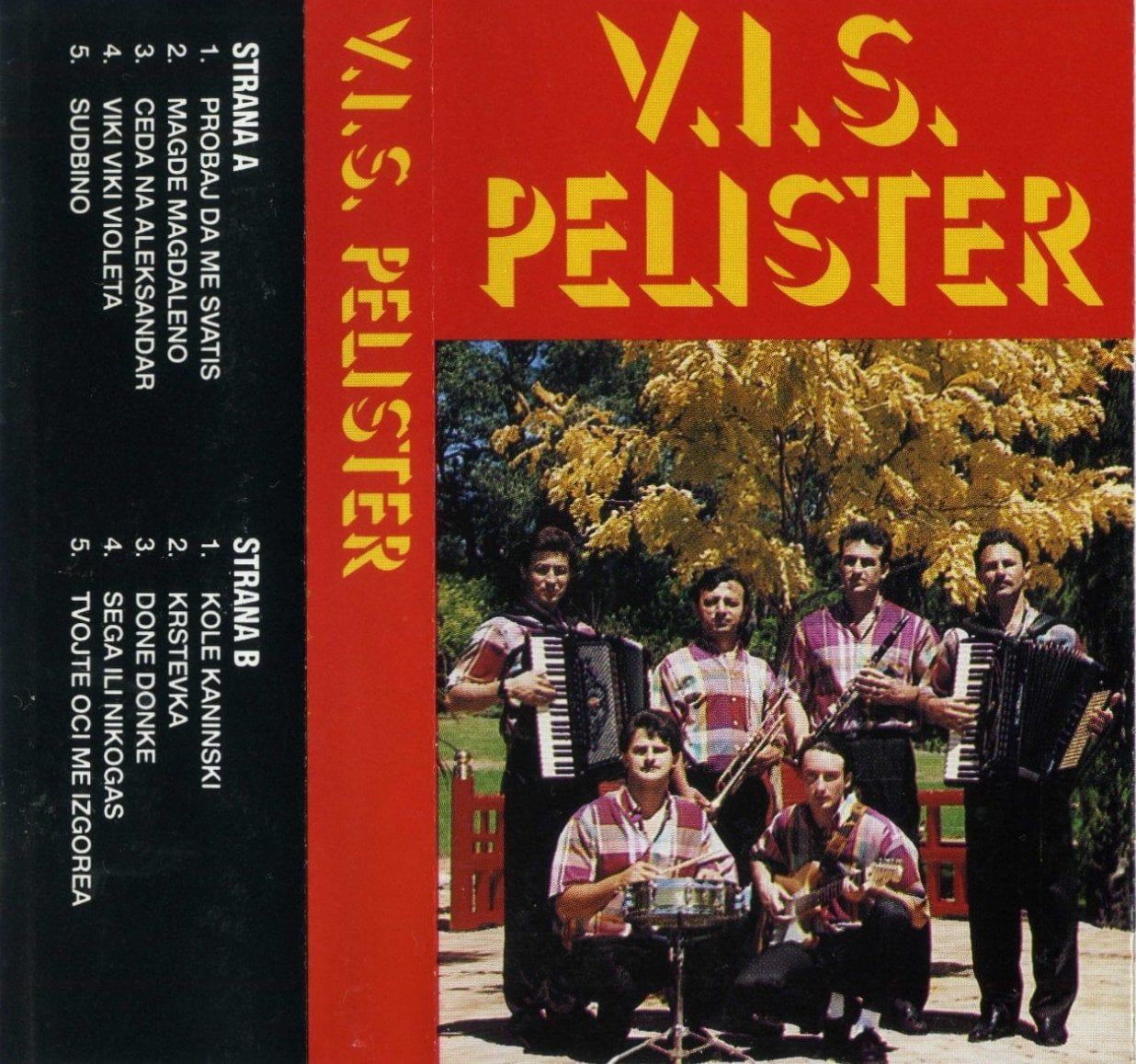

So when Dua Lipa said to the audience in Tirana, Albania that she now has “dy pasosha”, she used the term for “passport” in colloquial Albanian in ex-Yugoslavia, which comes from the Serbo-Croatian “pasoš”. For a time, “pasoš” was the word that appeared on every Yugoslav citizen’s passport. The term still means “passport” in Serbian, Bosnian, Montenegrin and Macedonian, but since independence in 1991, Croatian instead uses the prescriptivist term “putovnica” and Slovenian “potni list”.

Many Albanians throughout what was Yugoslavia will downplay it if asked but Yugoslav rule for over 8 decades saw colloquial Albanian in Kosovo, Montenegro and Macedonia adopt many Serbo-Croatian words and terms, particularly relating to administration, infrastructure and commerce — areas primarily of federal Yugoslav domain and therefore subject to nationwide standardisation. The same occurred to Slovenian and Macedonian, both being much closer related to Serbo-Croatian and official languages of Yugoslavia, and therefore adopted far more words and phrases than Albanian in ex-Yugoslavia.

Here are some examples of Serbo-Croatian words adopted into colloquial Albanian of ex-Yugoslavia:

- opshtinë (municipality)

- reshenje (legal resolution)

- porez (tax)

- carinë (customs)

- stanicë (station)

- zadrugë (collective)

Even some everyday items

- strujë (electricity)

- kaish (belt)

- vilushkë (knife)

- frizhider (refrigerator)

- sobë (room)

- pivë (beer)

- stan (apartment)

and many more.

Note that these are not standard terms and would rarely, if ever, be seen in official texts, but are heard in general speech or seen in informal communication such as in online comments.

There are also terms found in Albanian in Kosovo, Montenegro and Macedonia that conform or are consistent with their Serbo-Croatian equivalents, and not, or no longer, in use in Albania.

- One term is “shitore” for “shop”, consistent with the Serbo-Croatian “prodavnica”, both literally meaning “selling place”. The standard Albanian term is “dyqan”, from Turkish, a word also in Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, Montenegrin (đućan) and Macedonian (dukjan), but in many parts of ex-Yugoslavia is considered to be somewhat archaic or poetic.

- Another Turkish-origin word in ex-Yugoslav Albanian is “sahat” meaning “hour”. which is consistent with “sat/saat/sahat” used in Serbo-Croatian/BCSM and Macedonian. In standard Albanian, it’s the Latin/Greek “orë”.

- The same with “zejtin”, which despite also coming from the Turkish word for “olive”, in most of ex-Yugoslavia referred to sunflower or vegetable cooking oil, while its standard Albanian version for “cooking oil” is “vaj”, with the main form being olive oil.

- Another is "korzo" for "stroll" or "promenade". From Italian, it's a pan-Yugoslav term, as opposed to "xhiro" in standard Albanian.

That words will be adopted from the main language of administration is a worldwide linguistic phenomenon — just look at the amount of English legal terms there are in the languages of countries that were former British dependencies, Russian words in Central Asian languages or that Hebrew terms used at the numerous checkpoints (mahsom) in the West Bank have entered colloquial Palestinian Arabic.

Since Kosovo has been a separate entity no longer under Serbian administration for over 25 years, and with that Albanian totally supplanting Serbian in all aspects of public discourse, the increase in access and reach of the use of standard Albanian in all media, plus the push to remove all vestiges of occupation, the use of most of these Serbo-Croatian words by Albanians in Kosovo has seen a major decrease, but still many from the diaspora, such as Dua Lipa, who learnt a colloquial dialectal form of Albanian from the past still use these words, some often unaware of their origin.

The newest factor now has been the drawing of borders between what used to be the one wider Albanian-speaking cultural sphere in Yugoslavia. Now Albanian-speakers are in separate countries: Kosovo, Serbia, Montenegro and N. Macedonia, where the latter three have Slavic-speaking majorities, and so some of these Slavic-derived terms are still part of the talk on the street.

Is it “bad” that these words appear in these languages?

Not at all! It’s part of the dynamism of languages as they constantly come into contact with other languages and contexts. It’s only natural. These words are vestiges of history and even identity markers. Relatedly, purposefully eliminating these words won’t miraculously erase the errors of the past. Natural attrition will see many of these words go in the long-run anyway.

Urime Dua Lipa! Mirë se vjen në klubin e tre pasaportave… ose pasoshave!

.%20A%20day%20of%20campaigning%20%E2%99%80%20%E2%80%A6%20or%20a%20day%20to%20buy%20flowers%20%F0%9F%92%90.jpg)