I'm glad to announce that I have a, well, not-so-new translation speciality! Something that combines and extends beyond all my language, cultural and historical skills and knowledge.

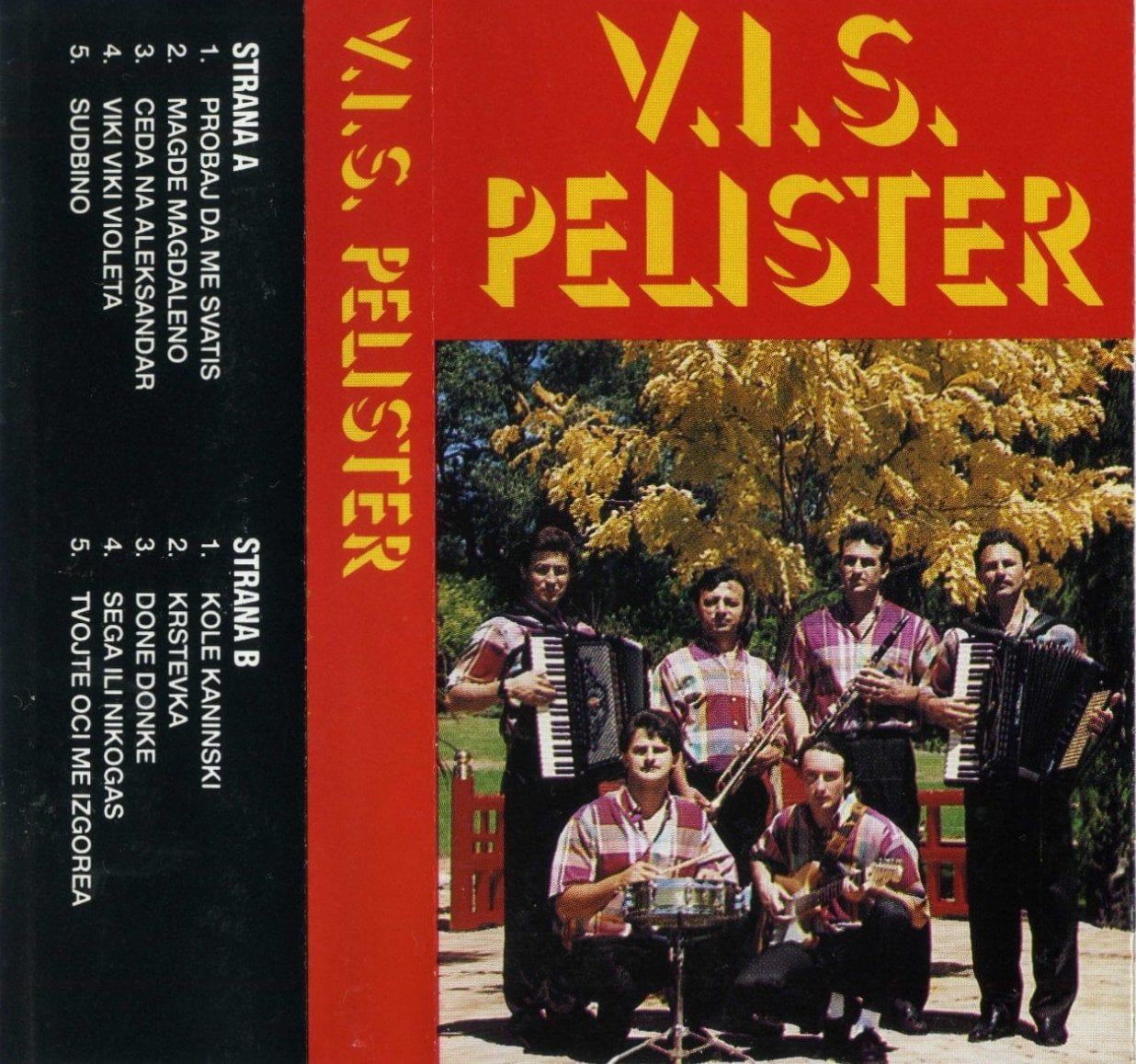

It's Macedonian genealogy translation!

And guess what? This is something that AI cannot do at all!

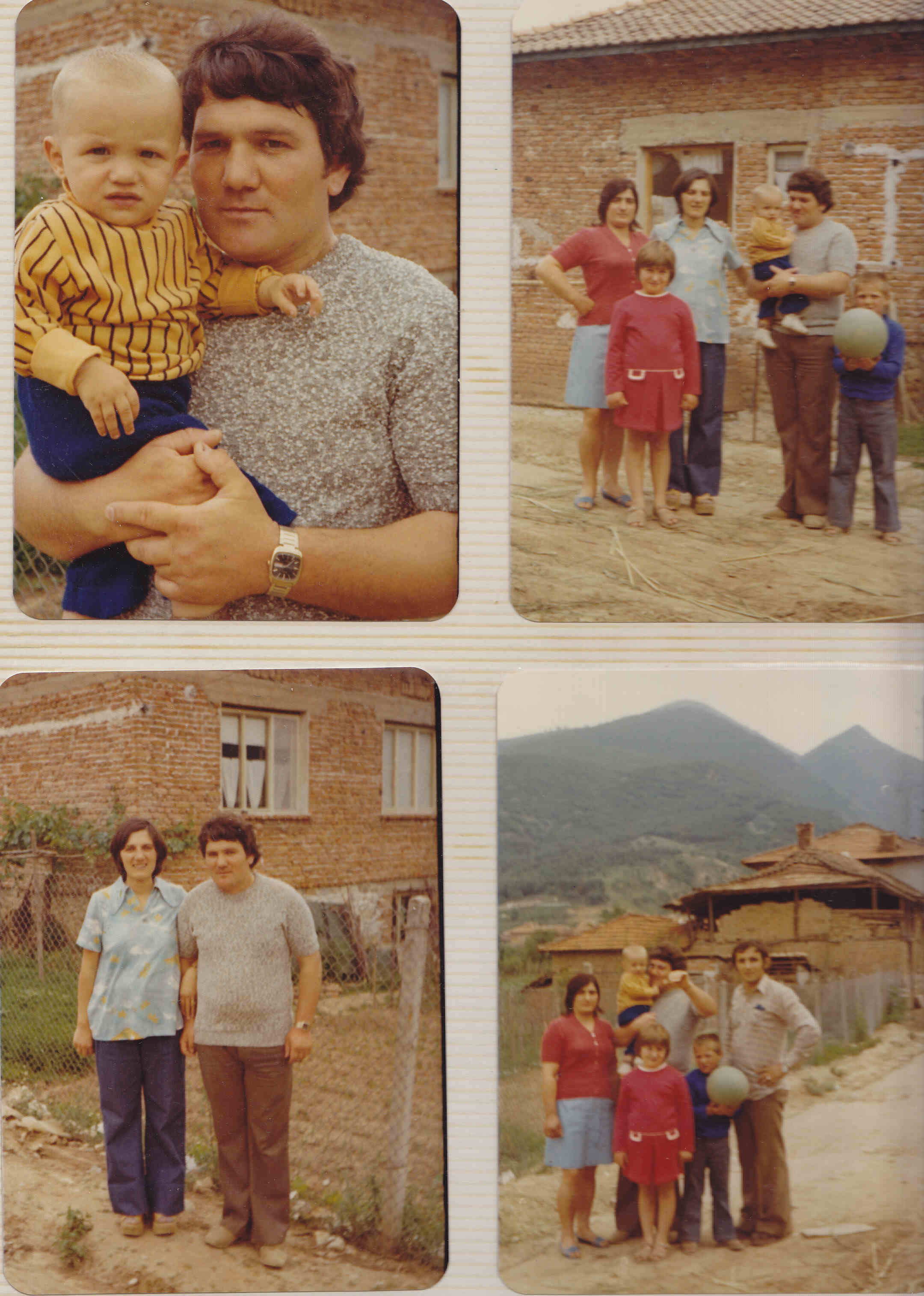

Over the past decade I have received a trickle of requests directly from many people in the USA, Canada and Australia tracing their family histories for letters and photos in often near-indecipherable handwriting to be translated. The common link is that these materials belong to family members and ancestors who came from Macedonia (all parts). These requests for translations in this field have increased exponentially over the past few years, so it's more of a speciality than just something on the side.

What makes translating these texts so special is that they can be in a number of languages and alphabets, sometimes even in the one sentence. The languages and scripts I have encountered include:

* Macedonian, in its standard form and in numerous dialects (written in the modern Macedonian Cyrillic, pre-1945 Bulgarian Cyrillic, Serbian Cyrillic, Latin or Greek alphabets)

* Greek (primarily Katharevousa prior to the 1970s, Demotika after that)

* Bulgarian (in both pre- and post-1945 Cyrillic alphabets)

* Serbian (Cyrillic and Latin alphabets)

* Albanian (usually in the Albanian Latin alphabet but once I had Albanian text written in the Greek alphabet)

* Ottoman Turkish (which is quite different from modern Turkish, and written in Perso-Arabic script)

* Modern Turkish (in Latin script and, rarely, even in Bulgarian or Macedonian Cyrillic)

* French (which was the language of bureaucracy in the final decades of the Ottoman Empire, plus the main international language used in the Balkans for most of the 20th century)

* German (in the 19th and early 20th centuries, many from the Balkan elite were educated in Austria and Germany)

* Aromanian (also known as Vlach, related to Romanian, and written in the Latin or Greek alphabets)

* Old Church Slavonic (particularly when involving church records and inscriptions)

* Russian (in pre-1918 and post-1918 Cyrillic alphabets)

Fortunately I have enough proficiency in most of these languages to be able to translate at least basic text.

But being able to recognise these languages is just one of the many skills required with genealogy-related translations.

What have I found to be the most important skill to have when doing genealogy translations?

It has to be patience!

The last lot of genealogy-related texts I translated involved a large amount of Greek handwriting on the back of a number of old photos from the 1920s to early 1950s. Most the text was faded, often in near-indecipherable handwriting (where everyone has their own quirks), and riddled with spelling mistakes and grammar errors, something typical for Greek, where there are, for instance, five letters or combinations that can represent the sound 'i'; plus being a very poor country at the time, literacy levels in Greece were not very high.

Deciphering the text first can at times take hours, and involves a large amount of thinking and calculation. It's much like deciphering hieroglyphics or the Rosetta Stone! So the key to success here is patience; very much like the tortoise beating the hare in Aesop's fable.That eureka moment when the text finally makes sense after solving the puzzle is so rewarding, and so too is when all of this effort has also provided priceless information about a person's past or even answered a long-unsolvable question.

Patience is a virtue!

Talking about Greek, knowing how to read Greek handwriting is a must for this field of translation! This is something I can do.

The official language of the Orthodox Church in the Ottoman Empire, and to this day for the Greek Orthodox Church, is a modern 'cleansed' version of Greek called 'Katharevousa' (Καθαρεύουσα). This was also the main language of instruction for the relatively few privileged Orthodox Christian children who were able to attend schools during the Ottoman Empire, particularly before the 1860s, resulting in Greek being the main literary language for Orthodox Christians who could read and write during that time.

This did not necessarily mean that everyone who wrote in Greek actually spoke or considered themselves to be Greek. The peoples of the Ottoman Empire were defined by their 'millet', i.e. self-governing religious community, rather than ethnicity. All Orthodox Christians were therefore officially 'Greeks' ('Rumlar' in Turkish, i.e. 'Romans', from the Greek 'Romoi', which is how Orthodox Christians in the Byzantine referred to themselves when the Turks arrived in Anatolia) regardless of what language they spoke.

With this in mind, having some knowledge of Greek is a must if doing genealogical and/or historical research for most of the Balkans, particularly before the 20th century, and naturally if it involves anything to do with territories where the Greek Orthodox Church had a presence. All records of births, marriages and deaths used to be the responsibility of the millet, i.e. church, mosque, synagogue, so for Orthodox Christians most of these records were usually in Greek.This also means having to read some pretty atrocious handwriting, but fortunately there are some resources available on the net to refer to. This site in particular has helped me decipher those weird squiggles and the dreaded abbreviated forms used for letter combinations often encountered in Greek handwriting.

Then there's the added factor that the Greek alphabet was used by some people to render their spoken languages such as Albanian/Arvanite, Aromanian/Vlach, Macedonian, Bulgarian, Gagauz, Turkish, Ladino, etc. As the Greek alphabet is limited in the sounds it represents, some rather creative letter combinations were improvised to render them (such as 'τσσ' for 'ch').

If you're wanting to start your search for your Macedonian ancestry, first stop would be to join Facebook groups such as Macedonian Ancestry and Early Macedonian Settlers, where there are plenty of other people who can help in patching your family history, especially if you have details of villages and people's names. Also, if you know your ancestral village, going direct to village-based Facebook groups are excellent places to ask for family details, and don't worry if you don't know Macedonian, Greek or Bulgarian as there is often (though not always) someone who knows English who can reply (especially if they're also in the diaspora).

However, it's not at all straightforward. Macedonia is not like the UK or Germany with its long tradition of recordkeeping.

Some pitfalls of Macedonian genealogy include:

- Lack of records due to past politics, war, ethnic cleansing, poor storage, etc. More often than not, most records prior to WWII simply don't exist.

- Prior to the 1950s, when recordkeeping became standardised, birth dates were never regarded as important. Often the birth date on record was the day of the birth's registration and not the actual birth, which could have happened many months earlier. Many older people simply didn't know when they were actually born and just made up birth dates. Some people didn't even know what year they were actually born (especially if born during times of war, such as WWI).

- Registrar officials in the Balkans ('matichari' in Macedonian) are generally unhelpful. Genealogy in the region is a rather foreign concept, so most locals really don't see what's the point of finding out about someone's past (unless you're wanting to claim property).

- Forced name changes due to assimilation policies created the situation where people would be known by one name in their native language but another (official) name in records. This is particularly the case in Greece where people of ethnic minorities (Macedonians, Aromanians, Albanians) would generally be known by a nickname in their native language but have a Greek name in all records. Often the Greek names bore little relation to the native names.

- Surnames were not standardised all throughout Macedonia until as late as the early 1950s. Until then, Macedonians would have a 'surname' ('prezime') often based on the name of the oldest male in the 'soy' (extended family or clan) at the time of birth. This resulted in siblings having different 'surnames' as that oldest male would change over time. In other cases, the 'surname' would be different depending on the time of entry in records (different surname in church records, military records, school records, etc.)

- Talking of the extended family, Macedonians used to be known by what 'soy' they belonged to. Knowing the name of your soy be very helpful and the names of which often formed the basis for modern surnames (in the western sense). However, these names are often not recorded anyway and are known from word of mouth. This is where the Facebook groups come in handy.

Nevertheless, if you have any questions about Macedonian genealogy or need any old texts translated, whether it be old letters, immigration documents or the inscriptions on the back of old photos, then do what many others have done and email me at info@nicknasev.com and I'll be glad to answer your queries.

.%20A%20day%20of%20campaigning%20%E2%99%80%20%E2%80%A6%20or%20a%20day%20to%20buy%20flowers%20%F0%9F%92%90.jpg)